Physical Exercise and Mental Health in Adolescents: Scoping Review

Ejercicio físico y salud mental en adolescentes: revisión de alcance

Nathali Carvajal Tello , Alejandro Segura-Ordoñez, Hilary Andrea Banguero Oñate, Juan David Hurtado Mosquera

Abstract

Objective. To identify the most implemented exercises and their prescription, in addition to the effects of exercise on mental health in adolescents.

Methods. A scoping review was performed from search of electronic databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Springer, Google Scholar, from 23/08/2023 to 01/01/2024 in English, Spanish, and Portuguese language, including randomized clinical trial and cohort type studies.

Results. A total of 7 articles were included: 57.14% controlled clinical trials, 100% in English. The number of participants was 85,637 aged 12 to 16 years. Intervention time ranged from 8 to 43 weeks, 2 to 5 times per week, 1 session per day, duration per session 10 to 120 minutes. The most used type of training was Programmed Physical Education followed by High Intensity Interval Training.

Conclusions. Exercises such as Programmed Physical Education, High Intensity Interval Training, Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity are included, which show positive effects on the increase in psychological well-being, quality of life and a significant decrease in anxiety and stress symptoms.

Keywords

Mental health; adolescents; physical activity; exercise.

Resumen

Objetivo. Identificar los ejercicios más implementados y su prescripción, además de los efectos del ejercicio en la salud mental de adolescentes.

Método. Se realizó una revisión de alcance a partir de búsqueda de bases de datos electrónicas: PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Springer, Google Académico, desde el 23/08/2023 hasta el 01/01/2024 en idioma inglés, español y portugués, incluyendo estudios tipo ensayos clínicos aleatorizados y cohortes.

Resultados. En total 7 artículos fueron incluidos: 57.14% ensayos clínicos controlados, 100% en inglés. El número de participantes fue 85.637 con edades entre 12 y 16 años. El tiempo de intervención osciló entre 8 a 43 semanas, 2 a 5 veces por semana, 1 sesión diaria, duración por sesión 10 a 120 minutos. El tipo de entrenamiento más utilizado fue Educación Física Programada, seguido del Entrenamiento de Intervalos de Alta Intensidad.

Conclusiones. Se incluyen ejercicios como Educación Física Programada, Entrenamiento de Intervalos de Alta Intensidad, Actividad física moderada a vigorosa, los cuales muestran efectos positivos en el aumento en el bienestar psicológico, calidad de vida y una disminución significativa en los síntomas de ansiedad y estrés.

Palabras clave

Salud mental; adolescentes; actividad física; ejercicio.

Introduction

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which each individual develops his or her potential, can cope with life's stresses, work productively and fruitfully, and contribute to his or her community [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescents as individuals in the 10-19 years age group, and estimates that 20% of adolescents worldwide suffer from some mental disorder [2]. Separation anxiety, attention deficit or social phobia are some of the most common disorders that can occur in children of any race or ethnicity [3].

Globally, it is estimated that 1 in 7 adolescents (14%) experience mental health conditions [4]. Mental health conditions such as anxiety and depressive disorders constitute a major burden of disease for adolescents worldwide [5]. About 15% of adolescents had a major depressive episode, 37% had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and 20% reported that they considered suicide [6]. As for sedentary lifestyle in adolescents, a significant relationship has been found with depressive symptomatology [7,8]. Behavioral disorders, social phobia, sadness, loss of interest in activities, changes in appetite and sleep, lack of concentration, loss of confidence, negative thoughts about the future, guilt or suicide are added [9,10].

To positively benefit the emotional and mental state of people, in addition to improving physical appearance and maintaining health, physical exercise, exercise, sport, play or recreation and Programed Physical Education (PPE) are proposed as a therapeutic strategy [11]. There are differences between the terms physical activity, exercise, sport, play or recreation and physical education class, which are defined below in order to facilitate understanding of the methodology and results of this study.

Exercise according to the WHO is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, and can be classified as mild, moderate and vigorous according to their intensity [12]. Exercise is a component of physical activity. The distinguishing characteristic of exercise is that it is a structured activity specifically planned to develop and maintain physical fitness [13]. Sport is a game that involves physical skills with a wide following and a wide level of stability [14]. Playing or recreation is at the heart of early years’ education and is central to children’s learning, as well as their physical, mental, social, and emotional health and well-being [15]. PPE is carried out in schools where at least 2 hours week specific activities are carried out to achieve developmental objectives related to physical fitness, health promotion, wellness and healthy lifestyles in students [16].

Adolescents who engage in regular physical activity can reduce anxiety, depression, stress levels, as well as improve mood, cognitive function, self-esteem and sleep habits [17]. Exercise and physical activity are tools that benefit physical and mental health, and a positive association with mental health interventions has been demonstrated [18]. Thus, there is a positive association between physical activity and a lower risk of developing physical and/or mental illness [19,20].

Given the above, the present scoping review delves into the parameters of physical exercise prescription and its effect on the mental health of adolescents, in order to expand the scientific evidence-based information on the exercises, dosage, and parameters of individualized exercise most appropriate for this population. In this way, to provide relevant information to health professionals who prescribe exercise, such as physical therapists, physical educators, and trainers. Therefore, the following question was posed: what are the parameters of exercise prescription and its effect on mental health in adolescents? The general objective of this research was to identify the most implemented exercises and their prescription, in addition to the effects of exercise on mental health in adolescents.

Methodology

Sources of information search

Research was analyzed in relation to the study variables and included cohort studies and controlled clinical trials from 2013 to 2023, from electronic databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Springer and a search engine Google Scholar, in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Terms were used for the search with combinations of Boléan operators: (mental health) AND (physical activity OR exercise OR physical exercise OR physical exercise) AND (child OR adolescent OR teen). Search equations are specified en Table 1.

Table 1. Information search equation.

| # | Database or Search Engine | Search Method | Search home | End search | Found articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Database: PubMed (Mesh terms) | (mental health) AND (physical activity OR exercise OR sport OR physical education class) AND (adolescent) | 23/08/2023 | 01/01/2024 | 301 |

| 2 | Database: Science Direct | 23/08/2023 | 01/01/2024 | 2214 | |

| 3 | Database: Scopus | 23/08/2023 | 01/01/2024 | 3207 | |

| 4 | Database: Springer | 23/08/2023 | 01/01/2024 | 3015 | |

| 5 | Search Engine: Google Scholar | 23/08/2023 | 01/01/2024 | 1290 |

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: studies conducted in adolescents, providing information on exercise prescription and its effect on mental health. Spanish, Portuguese, and English languages published between 2013-2023. Exclusion criteria: systematic reviews, case series, and case reports were not included.

Condition / Domain of the study: PICO Description

Participants/Population: Adolescents.

Intervention/Exposure: Exercise, sport.

Control group: PPE, play or recreation.

Results: Muscle strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility, body composition, mental health.

Data extraction (selection and coding)

The extraction of information from the articles was performed by two researchers (HB) and (JH). After this stage, the third author (NC) verified the agreements and disagreements of the articles. At this stage, studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified. Then, the articles were read in full text. The data obtained were related to the prescription of physical exercise in the mental health of adolescents, through the checklist proposed by PRISMA ScR [21].

Bias risk assessment (Quality)

After data collection, the agreement and disagreement of the content of the articles chosen by the investigators was confronted (HB), (JH), (NC). Discussion and call for the fourth author (AS) were carried out in cases of discrepancy. This avoided the risk of eligibility bias in the articles included. To assess the quality of the articles, we used the TESTEX scale, a tool for evaluating the quality of exercise training studies, which addresses crossover from sedentary control to exercise, periodic adjustment of exercise training intensity with respect to adaptation to physical training, and reporting of exercise program characteristics. It consists of 12 criteria, some of which have more than one possible point, for a maximum score of 15 points (5 points for study quality and 10 for reporting) [22].

Data synthesis strategy

A search strategy was developed for the databases, studies were located from which, when filtering by year, in the first choice of studies was made based on title and abstract and duplicates were discarded. Selection process: a matrix was created in Microsoft Excel and filtered by phases. Phase 1 included: identification, title, abstract, type of study. Phase 2: identification, title, abstract, journal data, type of study, study objective and abstract, including yes/no, reason for exclusion.

A qualitative summary of the studies was carried out in relation to the characteristics of the study population: number of participants, databases, language. Exercise prescription parameters: frequency, duration, intensity, progression, volume, type of exercise and effects of exercise on mental health in aspects such as quality of life, functionality and physical qualities such as muscular strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility, and body composition.

Categories of analysis

Frequency: number of repetitions per unit of time of any periodic process [23,24]. Duration: number of minutes of training required per session [25,26]. Intensity: degree of effort that an exercise demands on the person [27]. Volume: includes the amount of activity performed and includes the distance covered, the number of repetitions of an exercise and duration [28]. Progression: adaptation to effort, intensity, duration, and frequency [29]. Types of exercise: aerobic, flexibility, strength or endurance [30]. Muscle strength: capacity of the muscle to exert tension against a load during muscle contraction [31]. Aerobic capacity: physiologically, it is the ability to produce work using oxygen [32]. Flexibility: capacity of the joints to perform movements with the greatest possible amplitude without causing damage [33]. Body composition: indicator of health and physical condition of individuals [34]. Mental health: a primary good, the psychological preconditions for pursuing any conception of the good life, including well-being [35].

Main results

Physical exercise prescription: components of physical exercise prescription: frequency, duration, intensity, volume, progression, type of exercise, muscle strength. Effects on mental health and other variables such as muscle strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility and body composition.

Strategy for data synthesis

A qualitative summary of the selected articles was applied. A heterogeneous variation in the outcome measures currently used in the prescription of exercise and its effect on mental health in children and adolescents could be executed. Therefore, a narrative synthesis of the included study designs, number of participants, population characteristics, language, study variables, and databases was performed. The data synthesis was carried out following the SWIM guide [36], for synthesis without meta-analysis.

Results

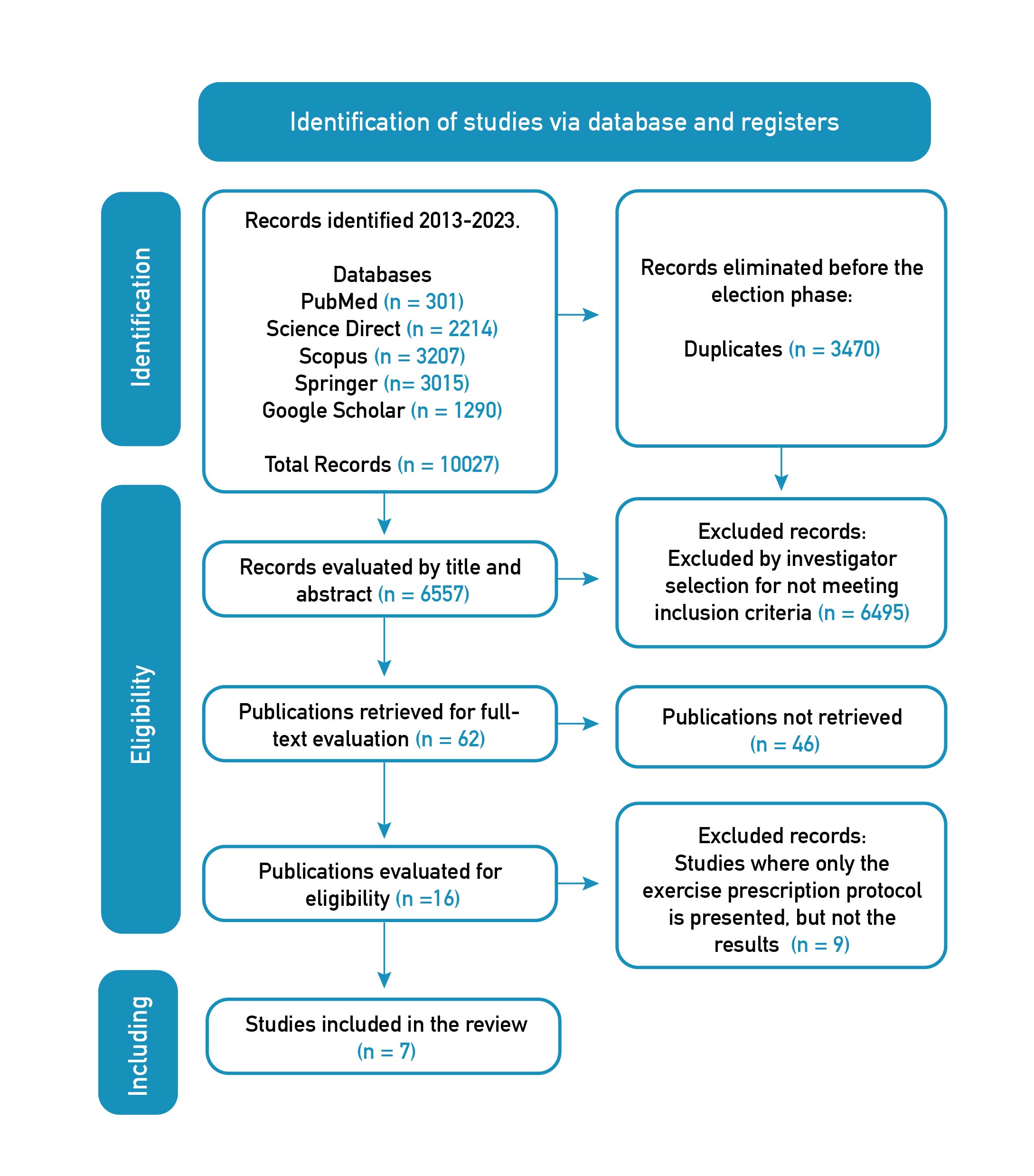

The literature reviewed allowed the registration of 10027 studies from the databases, 3470 duplicate articles were eliminated before the election phase, in total 6557 records were evaluated by title and abstract where 6495 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 62 articles for full text review, of which 46 were not retrieved, of the 16 studies evaluated in full text for eligibility 9 were excluded. Finally, 7 articles were selected for analysis in this scoping review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram.

Characteristics of the bibliography

Of the 7 included studies 90% n = (6) were found in the Pubmed database, 57% Controlled Clinical Trials (CCT) n = 4 and 43% Cohort Studies (CS) n = (3). 60% (3) From the European continent, followed by Oceania n = (2) and Asia n = (2), with 20%, respectively. In English language 100% n = (7) (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of the bibliography.

| # | Authors | Title | Database | Journal | Scimago Quartile | Type of study | Country | Continent | Language | Year | Objetive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costigan et al. [37] | HIIT training for cognitive and mental health in adolescents | Pubmed | Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise | Q1 | CCT | Australia | Oceania | English | 2016 | To evaluate the efficacy of two HIIT protocols for improving cognitive and mental health outcomes. |

| 2 | Wassenaar et al. [38] | Effect of a vigorous physical activity intervention on physical fitness, cognitive performance, and mental health in young adolescents | Springer | International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity | Q1 | CCT | United Kingdom | Europe | English | 2021 | To investigate whether a HIIT physical activity intervention delivered during school physical education could improve performance. |

| 3 | Frömel et al. [39] | Academic stress and physical activity in adolescents | Pubmed | BioMed Research International | Q2 | CC | Czech Republic | Europe | English | 2020 | Exploring associations between academic stress in adolescent boys and girls and their physical activity. |

| 4 | Ho et al. [40] | Youth development program based on sports, mental health and physical fitness for adolescents | Pubmed | Pedriatrics | Q1 | CCT | China | Asia | English | 2017 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a sports program based on positive youth development. |

| 5 | Eather et al. [41] | Effects of exercise on mental health outcomes in adolescents. | Science Direct | Psychology of Sport and Exercise | Q1 | CCT | Australia | Oceania | English | 2016 | To investigate the effectiveness of the CrossFit resistance training program. |

| 6 | Zhang et al. [42] | Muscle strengthening exercise and positive mental health in children and adolescents | Pubmed | Frontiers in Psychology | Q2 | CC | China | Asia | English | 2022 | To investigate the association between MSE with subjective well-being and resilience. |

| 7 | Bell et al. [43] | Relationship between physical activity, mental well-being and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents | Pubmed | International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity | Q1 | CC | United Kingdom | Europe | English | 2019 | Investigating whether physical activity is associated with improved mental well-being. |

Note. Abbreviations: Controlled Clinical Trial (CCT), Cohort Study (CC), High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Muscle Strengthening Exercises (MSE).

General characteristics of the adolescents

The total number of participants was 85,637 with ages ranging from 12.32 (23) to 16.43 (26). Sex was specified in 85,572 subjects of which 50.33% n = (43,071) were male. Additional information on the weight of the participants, as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. General characteristics of adolescents.

| # | Authors | n | F/M | EG/CG | Age (years) | BMI kg·m− 2 | Inclusion features | Exclusion features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costigan et al. [37] | 65 | NS | EG= 23/ AEP=21 EEP=22 | 15.5 +/- 0.6 | 22.08 +/- 3.56 | Informed consent | NS |

| 2 | Wassenaar et al. [38] | 16.017 | EG= F= 4.466 M= 3.530 CG= F=4.495 M=3.526 | EG= 7860 CG= 8157 | GE= 12.5 (0.296) GC= 12.5 (0.293) | NS | NS | NS |

| 3 | Frömel et al. [39] | 586 | F=399 M=187 | NA | M= 16.43 SD 1.17 F=16.39 SD 1.17 | M= 22.04 SD 3.30 F= 21.11 SD 3.14 | Participants with three sports sections in school, 120 minutes of extracurricular time. | NS |

| 4 | Ho et al. [40] | 664 | F=386 M=278 | EG= 331 CG=333 | EG= 12.32 (0.76) CG= 12.26 (0.75) | EG= N=232 (70.1) UW=8 (2.4) OW=73 (22.1) O=18 (5.4) CG= N=236 (70.9) UW=10 (3.0) OW=68 (20.4) O=19 (5.7) | Participate in 2 extracurricular activities at school. | Medical conditions |

| 5 | Eather et al. [41] | 96 | F=50 M=46 | EG=51 CG=45 | 15.4 SD 0.50 | NS | Completion of pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, training program and physical measurements. | NS |

| 6 | Zhang et al. [42] | 67.281 | F=32.362 M=34.919 | NA | 13.04 | N=72.5 OW=12.3 O=15.2 | Students from fifth to eighth grade, with good reading and comprehension skills, willing to answer the surveys. | Students whose teachers did not want them to take the survey or did not think they were appropriate to take the survey. |

| 7 | Bell et al. [43] | 928 | F= 343 M=330 | NA | 12.69 SD 0.34 | NE | Participation in the AHEAD trial and continued study attendance three years later. | Failure to complete the questionnaire. Dropping out of school during follow-up. Student's parent opted out, absence, illness or death of student. |

Note. Abbreviations: Not Specified (NS), Not Applicable (NA), Experimental Group (EG), Control Group (CG), Male (M), Female (F), Standard Deviation (SD), Aerobic Exercise Program (AEP), Endurance Exercise Program (EEP), Normal (N), Underweight (UW), Overweight (OW), Obesity (O), Adolescent Healthy Eating Activity and Intervention (AHEAD).

Description of exercise prescription

In the exercise prescription of the 7 included studies, 57.14 % included a control and experimental group, used as type of training: Programmed Physical Education (PPE), Aerobic Exercise Program (AEP), High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) = gross motor cardiorespiratory exercises. Endurance Exercise Program (EEP), HIIT = combination of cardiorespiratory and body weight resistance training exercises, Vigorous Physical Activity (VPA), PPE, and Crossfit. The 42.86% being studies that did not include EG, used as type of training: activities performed during school recess, muscle strengthening exercises, regular physical activity. The intensity was moderate-high in 57.14% n = (4), high in 28.57% n = (2) and in one study it was not specified. The sessions were performed once a day, in 2 articles it was not mentioned. Times per week ranged from 3 to 5; the number of weeks ranged from 8 to 43. The minutes ranged from 10 to 120 per session (Table 4).

Table 4. Description of exercise prescription.

| # | Authors | Type of training | Phases | Intensity | Sessions per day/times per week | Number of weeks | Session duration in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costigan et al. [37] | CG= PPE + usual activities AEP HIIT= gross motor cardio-respiratory exercises. EEP HIIT= combination of cardiorespiratory and body weight resistance training exercises. | HIIT sessions ranged from 8 to 10 min in duration (weeks 1 to 3: 8 min; weeks 4 to 6: 9 min; weeks 7 to 8: 10 min), with a work-to-rest ratio of 30:30 s. | High | 1/3 | 8 | 10 |

| 2 | Wassenaar et al. [38] | CG= PPE + usual activities, EG= VPA - HIIT | HIIT sessions were short or longer sets (from <45 s to 2-4 min) of high-intensity exercise interspersed with periods of rest or light activity. 4 min of VPA as part of a 10-min active warm-up and three 2-min VPA infusions per hour. | High | 1/5 | 43 | 20 |

| 3 | Frömel et al. [39] | CG= PPE EG= PFE + 2 sports | NS | Moderate - High | 1/3 | 16 | 120 |

| 4 | Ho et al. [40] | CG= Activities carried out during the school break | Warm-up phase, core sport activity (basketball, volleyball, kickboxing), technical phase of the sport, reflection phase and activity feedback. | Moderate - High | 1/5 | 18 | 90 |

| 5 | Eather et al. [41] | CG= PPE + sport EG= EFP + Cross Fit | Dynamic warm-up (10 min), a technique-based skill session (10 min), a core activity (10-20 min) and a stretching session (5 min). | Moderate - High | 1/2 | 8 | 120 |

| 6 | Zhang et al. [42] | CG= Muscle strengthening exercises | NS | NS | NS | NS | 20 |

| 7 | Bell et al. [43] | CG= Regular physical activity | NS | Moderate - High | NS | NS | 60 |

Abbreviations: Non-Specific (NS), High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Aerobic Exercise Program (AEP), Endurance Exercise Program (EEP), Vigorous Moderate Physical Activity (VPA), Programmed Physical Education (PFE).

Effects of physical exercise in adolescents

The findings of the measurements made in relation to the variables: mental health, muscle strength, aerobic capacity flexibility and body composition, using different questionnaires, and assessment tools, were captured in Table 5. Mental health was evaluated in 5 studies [37,38,40,41,43], by measuring executive function, flourishing scale (Psychological Well-being), psychological disorder, psychosocial problems, psychological assets, social assets (family connectedness, school connectedness), Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), Relational Memory Task, mental component, Skills and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ TDS), SDQ subscale, behavioral problems, hyperactivity, peer problem, and prosocial behavior.

Table 5. Effects of physical exercise in adolescents.

| # | Authors | Measurements | Basal | Posterior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costigan et al. [37] | Executive Function | CG= 34.25 (25.07 - 43.45) | CG= 34.95 (26.41 - 43.49) |

| EG (AEP)= 36.05 (28.28 - 43.83 ) | EG (AEP)= 32.80 (24.69 - 40.91) |

|||

| CG= 1.46 (0.98 - 1.94) | CG= 1.63 (1.09 - 2.17) | |||

| EG (AEP)= 1.99 (1.49 - 2.48) | EG (AEP)= 2.18 (1.62 - 2.73) |

|||

| EG (EEP)= 2.40 (1.92 - 2.88) | EG (EEP)= 2.01 (1.47 - 2.55) |

|||

| CG= 57.87 (47.2 - 68.54) | CG= 57.32 (47.43 - 67.21) | |||

| EG (AEP)= 63.21 (54.10 - 72.33) | EG (AEP)= 55.97 (46.80 - 65.14) |

|||

| EG (EEP)= 65.07 (56.24 - 73.91) | EG (EEP)= 53.79 (44.50 - 63.08) |

|||

| Flourishing scale (psychological well-being) | CG= 48.27 (46.16 - 50.38) | CG= 47.00 (44.22 - 49.78) | ||

| EG (AEP)= 46.38 (44.17 - 48.59) | EG (AEP)= 47.92 (44.92 - 50.91) |

|||

| EG (EEP)= 46.59 (44.48 - 48.70) | EG (EEP)= 48.28 (45.36 - 51.20) |

|||

| Psychological Disorder | CG=22.05 (18.87 - 25.23) | CG= 22.10 (18.83 - 25.36) | ||

| EG (AEP)= 18.60 (15.27 - 21.94) | EG (AEP)= 18.17 (14.74 - 21.59) |

|||

| EG (EEP)= 17.68 (14.50 - 20.86) | EG (EEP) =17.55 (14.31 - 20.78) |

|||

| Average physical self-description score (Appearance) | CG= 4.49 (3.92 - 5.06) | CG= 5.00 (4.52 - 5.48) | ||

| EG (AEP)= 4.09 (3.49 - 4.68) | EG (AEP)= 4.69 (4.19 - 5.19) |

|||

| EG (EEP)= 3.52 (2.95 - 4.09) | EG (EEP)= 4.35 (3.88 - 4.83) |

|||

| Mean physical self-description score (Global physical) | CG= 5.00 (4.52 - 5.48) | CG= 5.04 (4.54 - 5.54) | ||

| EG (AEP)= 4.69 (4.19 - 5.19) | EG (AEP)= 4.71 (4.19 - 5.24) |

|||

| GE (EEP)= 4.35 (3.88 - 4.83) | GE (EEP)= 4.41 (3.91 - 4.91) |

|||

| 2 | Wassenaar et al. [38] | 20 Msr (Fittnes, turns) | CG= 37.85 (20.65) | CG= 36.11 (20.75) |

| EG= 37.85 (20.65) | EG= 41.36 (21.95) | |||

| Reaction time task (RT3, ms) | CG= 380.21 (89.7) | CG= 376.07 (95.94) | ||

| EG= 378.7 (86.65) | EG= 378.58 (99.46) | |||

| Relational memory task (Accuracy %) | CG= 59.76 (12.24) | CG= 60.78 (13.08) | ||

| EG= 59.75 (11.93) | EG= 59.53 (13.05) | |||

| Two back task (Accuracy %) (RT3, ms) | CG= 53.4 (18.74) | CG= 55.48 (20.99) | ||

| EG= 54.43 (18.46) | EG= 55.24 (20.9) | |||

| CG= 844.17 (171.04) | CG= 799.45 (174.9) | |||

| EG= 857.67 (164.84) | EG= 802.26 (175.03) | |||

| Flanker task (Accuracy congruent %) | CG= 81.91 (16.81) | CG= 84.55 (16.44) | ||

| EG= 82.83 (17.14) | EG= 84.21 (16.57) | |||

| Flanker task (Inconsistent accuracy %) | CG= 60.02 (19.55) | CG= 63.06 (19.65) | ||

| EG= 60.22 (20.67) | EG= 62.2 (20.33) | |||

| Flanker task (RT3 congruent, ms) | CG= 490.35 (94.51) | CG= 479.19 (81.26) | ||

| EG= 490.26 (92.13) | EG= 476.82 (84.22) | |||

| Flanker task (RT3 incongruent, ms) | CG= 548.15 (126.16) | CG= 541.25 (109.06) | ||

| EG= 552.9 (127.12) | EG= 537.89 (108.67) | |||

| Color and shape change task (Accuracy without switch, %) | CG= 72.88 (17.25) | CG= 75.61 (17.48) | ||

| EG= 73.27 (17.21) | EG= 75.18 (17.61) | |||

| Color and shape change task (Accuracy change, %) | CG= 69.36 (17.15) | CG= 71.56 (17.59) | ||

| EG= 69.51 (16.89) | EG= 71.47 (17.65) | |||

| Color and shape change task (Without switch RT3, ms) | CG= 051.07 (337.52) | CG= 970.87 (318.08) | ||

| EG= 1075.67 (352.18) | EG= 974.95 (320.46) | |||

| Color and shape change task (RT3 switch, ms) | CG= 1404.21 (569.5) | CG= 1321.97 (544.16) | ||

| EG= 1452.99 (602.23) | EG= 1331.63 (562.05) | |||

| Psychosocial problems (Internalization score) | CG= 5.07 (3.49) | CG= 5.25 (3.6) | ||

| EG= 5.1 (3.56) | EG= 5.47 (3.72) | |||

| Psychosocial problems (Outsourcing score) | CG= 6.29 (3.74) | CG= 6.45 (3.8) | ||

| EG= 6.34 (3.85) | EG= 6.73 (3.78) | |||

| Self-esteem (Global) | CG= 4.43 (0.9) | CG= 4.3 (0.97) | ||

| EG= 4.39 (0.94) | EG= 4.23 (1.03) | |||

| Self-esteem (Physical) | CG= 4.44 (1.27) | CG= 4.14 (1.36) | ||

| EG= 4.36 (1.31) | EG= 4.07 (1.41) | |||

| 3 | Frömel et al. [39] | Physical Activity (min/hour -1) | M/WAS: 34.57 M/AS: 37.01 - F/WAS: 31.06 F/AS: 30.60 | M/WAS: 22.91 M/AS: 22.12 - F/WAS: 24.22 F/AS: 24.28 |

| Step . hour (numbers) | M/WAS: 1081 M/AS: 1160 - F/WAS: 961 M/CEA: 936 | M/WAS: 661 M/AS: 716 - F/WAS: 670 F/AS: 814 |

||

| MVPA ≥ 3 METs (min·hour-1) | M/WAS: 4.20 M/AS: 5.08 - F/WAS: 3.00 M/CEA: 3.30 | M/WAS: M/AS: 4.22 - F/WAS: 3.00 F/AS 4.35 P |

||

| MVPA≥ 60% HRmax (min) | M/WAS: 0.50 M/AS: 1.50 - F/WAS: 1.12 M/CEA: 1.64 | M/WAS: 0.47 M/AS: 1.53 - F/WAS: 0.59 M/CEA: 0.65 |

||

| 4 | Ho et al. [40] | Health-related quality of life (1 week before the intervention) | Physical component score CG= 49.87 (5.77) EG= 49.59 (6.51) | CG= 51.57 (5.70) EG= 51.49 (6.64) |

| Mental component score CG= 47.16 (9.16) EG= 47.16 (9.16) | CG= 46.15 (9.59) EG= 48.41 (8.33) |

|||

| BMI score CG= 0.48 (1.16) EG= 0.54 (1.15) | CG= 0.60 (1.10) EG= 0.57 (1.07) |

|||

| Body fat ratio (%) CG= 20.51 (7.93) EG= 19.90 (8.41) | CG= 21.28 (8.75) EG= 19.89 (9.18) |

|||

| Health-related physical fitness (1 week before intervention) | One-minute bending test (time) CG= 22.91 (14.00) EG= 21.47 (12.19) | CG= 32.10 (13.26) EG= 30.81 (12.62) |

||

| Total grip force (kg) CG= 39.70 (11.97) EG= 40.42 (12.33) | CG= 38.75 (14.64) EG= 40.89 (14.85) |

|||

| Test Sit-and-reach (cm) CG= 28.42 (8.13) EG= 27.16 (9.29) | CG= 25.24 (8.15) EG= 27.79 (9.58) |

|||

| One-minute abdominal test (time) CG= 27.59 (7.78) EG= 28.75 (8.34) | CG= 31.21 (9.52) EG= 31.03 (10.74) |

|||

| Standing long jump test (cm) CG= 130.98 (24.21) EG= 132.96 (27.16) | CG= 131.97 (30.33) EG= 136.92 (24.89) |

|||

| Average balancing test Y (m) CG= 1.26 (0.20) EG= 1.28 (0.24) | CG= 1.30 (0.29) EG= 1.36 (0.27) P: 0.01 | |||

| Psychological assets (1 week before intervention) | Self-efficacy CG= 27.88 (6.10) EG= 27.21 (6.63) | CG= 28.45 (6.21) EG= 29.69 (4.92) |

||

| Resilience CG= 64.13 (16.36) EG= 63.76 (18.39) | CG= 65.43 (17.76) EG= 68.37 (13.15) |

|||

| Social assets (1 week prior to intervention) | Family connection CG= 43.73 (9.38) EG= 42.73 (9.56) | CG= 43.23 (9.07) EG= 41.80 (9.85) |

||

| School connectivity CG= 23.91 (4.99) EG= 23.35 (4.82) | CG= 22.50 (5.03) EG= 22.36 (5.23) |

|||

| Physical activity level (1 week before the intervention) | CG= 23.35 (4.82) EG= 5.42 (2.79) | CG= 5.10 (2.75) EG= 6.10 (2.20) |

||

| 5 | Eather et al. [41] | Perceived body fat | CG (M)= 4.83 (1.52) (F)= 3.82 (1.29) EG (M)= 5.05 (1.48) (F)= 4.00 (1.42) | CG (M)= 4.52 (1.13) (F)= 3.73 (1.40) EG (M)= 5.23 (1.12) |

| Total difficulty score | CG= 9.63 (3.86) EG= 10.04 (0.42) | CG= 9.34 (4.03) EG= 11.04 (5.23) |

||

| Global self-esteem (No risk of psychological distress) | CG= 4.74 (0.85) EG= 4.89 (0.73) | CG= 4.94 (0.99) EG= 4.91 (0.80) |

||

| Physical self-concept (No risk of psychological distress) | CG= 3.93 (1.08) EG= 4.06 (0.87) | CG= 4.19 (1.00) EG= 4.09 (1.07) |

||

| Perceived body fatness (No risk of psychological distress) | CG= 4.49 (1.41) EG= 4.69 (1.27) | CG= 4.22 (1.36) EG= 4.64 (1.38 |

||

| Perceived Appearance (No risk of psychological distress) | CG= 3.91 (1.27) EG= 4.07 (0.94) | CG= 4.02 (1.14) EG= 4.140 (1.15) |

||

| Total difficulty score | CG= 19.71 (2.73) EG= 21.00 (3.16) | CG= 19.80 (5.35) EG= 17.50 (6.78) |

||

| Global self-esteem (At risk for psychological distress) | CG= 3.69 (1.43) EG= 3.33 (1.08) | CG= 3.43 (1.59) EG= 3.80 (1.14) |

||

| Physical self-concept (At risk for psychological distress) | CG= 3.22 (1.30) EG= 2.79 (0.94) | CG= 2.86 (1.24) EG= 3.35 (0.88) |

||

| Perceived body fat (At risk for psychological distress) | CG= 4.24 (1.64) EG= 3.19 (1.51) | CG= 4.08 (1.59) EG= 3.81 (1.42) P: 0.042 | ||

| Perceived appearance (At risk of psychological distress) | CG= 3.09 (1.29) EG= 2.81 (0.93) | CG= 3.13 (1.34) EG= 3.33 (1.22) |

||

| 6 | Zhang et al. [42] | Muscle strengthening exercise days (continuous) | Day 1= 0.42, Day 2= 0.76, Day 3= 1.00, Day 4= 1.38, Day 5= 1.55, Day 6= 1.84, Day 7= 2.17 | Day 1= 0.69, Day 2= 1.42, Day 3= 1.97, Day 4= 2.80, Day 5= 3.07, Day 6= 3.80, Day 7= 4.66 |

| Muscle-strengthening exercise days (2 cuts) | 3-5 days= 0.86, 6-7 days= 1.74 | 3-5 days= 1.78, 6-7 days= 3.83 | ||

| Muscle strengthening exercise guidelines | Not found: 0, found: 1.02 | Not found: 0, found: 2.17 | ||

| 7 | Bell et al. [43] | Overall score of WEMWBS | −0.02 (− 0.44 - 0.40) | −0.06 (− 0.47 - 0.35) t = − 0.27 |

| SDQ TDS Questionnaire | - 0.16 (− 0.41 - 0.09) | 0.04 (− 0.24 - 0.32) t = 0.29 |

||

| Emotional problems (SDQ Subscale) | −0.11 (− 0.23 - − 0.00) | −0.12 (− 0.24 − 0.01) t = − 2.09 |

||

| Behavioral problems | − 0.02 (− 0.10 - 0.60) | 0.06 (− 0.03 - 0.14) t = 1.29 |

||

| Hyperactivity | 0.02 (− 0.09 - 0.14) | 0.13 (0.01 - 0.26) t = 2.18 |

||

| Pair problem | -0.02 (− 0.09 - 0.05) | − 0.02 (− 0.09 - 0.06) t = − 0.44 |

||

| Prosocial behavior | 0.09 (0.00 - 0.19) | 0.01 (− 0.08 - 0.10) t = 0.26 |

Note. Abbreviations: CG: Control group, EG: Experimental group, M: Male, F: Female, BMI: Body mass index, Kg: Kilograms, cm: Centimeters, m: Meters, AEP: Aerobic Exercise Program, RAP: Endurance Exercise Program, M/WAS: Men Without Academic Stress. M/AS: Men with Academic Stress. F/WAS: Female Without Academic Stress, F/AS: Women with Academic Stress. Min: Minutes. Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA), Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), Relational Memory Task, mental component, Skills and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ TDS).

The post-intervention results found were not significant for the study by Costigan et al. [37]. Wassenaar et al. [38] found no P-value specification. Ho et al. [40] found statistically significant post-intervention results in the mental component score and psychological assets (Self-efficacy and resilience). Eather et al. [41] found significance in the physical self-concept test. Meanwhile, Bell et al. [43] was significant for the SDQ subscale, assessment of behavioral problems, and hyperactivity.

Muscle strength was assessed in the study by Ho et al. [40], using standing longitudinal jump test, one-minute push-up test, total grip strength measurements, and one-minute sit-up test. Only the standing longitudinal jump test measured in centimeters was significant after the intervention. 3 of the 7 studies performed aerobic capacity assessment [38-40], by means of 20mrs (Fitness Laps), reaction time task (RT3 ms), physical activity (min/hour/), steps/hour (numbers), VPA (Vigorous Physical Activity) ≥ 3 METs (min/hour), VPA≥ 60% HRmax (min) physical activity level. Of these tests, the ones that yielded statistically significant post-intervention information were Steps/hour (numbers) VPA ≥ 3 METs (min/hour), and physical activity measurement.

The study that evaluated flexibility was the one by Ho et al. [40] with the sit-and-reach test, showing statistically significant results 1 month after the intervention. Body composition was assessed in 2 of the studies, the study by Ho et al. [40] by means of health-related quality of life (BMI score and body fat ratio). Meanwhile, Eather et al. [41] assessed perceived body fatness (at risk and not at risk for psychological distress), neither of these studies showed post-intervention significance.

Methodological quality of the studies

All studies were evaluated with the TESTEX scale described in Table 6. According to the interpretation of the scale, Zhang et al. [42] and Bell et al. [43] obtained a score of 15, Frömel et al. [39] was qualified with 14, Costigan et al. [37] with 13, Ho et al. [40] and Eather et al. [41] rated with 11, respectively, and finally Wassenaar et al. [38] with 10.

Table 6. TESTEX Scale.

| # | Authors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costigan et al. [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| 2 | Wassenaar et al. [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 3 | Frömel et al. [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| 4 | Ho et al. [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 5 | Eather et al. [41] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 6 | Zhang et al. [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| 7 | Bell et al. [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

Note. TESTEX scale criteria: Study quality (1) Eligibility criteria specified (1 point), (2) Randomization specified (1 point), (3) Allocation concealment (1 point), (4) Groups similar at baseline (1 point), (5) Blinding of assessor (for at least one key outcome) (1 point). Study reporting (6) Outcome measures assessed in 85% of patients (3 points possible), (7) Intention to-treat analysis (1 point), (8) Between-group statistical comparisons reported (2 points possible), (9) Point measures and measures of variability for all reported outcome measures (1 point), (10) Activity monitoring in control groups (1 point), (11) Relative exercise intensity remained constant (1 point), (12) Exercise volume and energy expenditure (1 point). Total out of possible: 15 points.

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to identify the most implemented exercises and their prescription, in addition to the effects of exercise on mental health in adolescents. According to the results of 7 studies, with a total of 85,637 participants, there are findings showing that adequate exercise prescription with moderate participation in physical activities with strength exercises, habitual AEP activities, HIIT, gross motor cardiorespiratory exercises, EEP, combination of cardiorespiratory and body weight resistance training exercises, VPA and crossfit, are associated with an increase in general psychological well-being, perceived quality of life and a significant decrease in symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress. Considering that not all the studies and their measurements yielded significant results, it is advisable to conduct more in-depth searches in this field with more representative samples, which will allow reinforcing the scientific evidence that more precisely supports the intervention with respect to the types of exercises, their parameters and prescription. In this way, its positive effect on mental health can be better validated.

It is important to highlight that in our study, 60% of the articles included correspond to the European continent, followed by Asia and Oceania with 20%, respectively. No articles were found from the American continent, and 100% of the articles were in English. In the United States, it has been reported that adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17, 36.7% had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, 18.8% seriously considered attempting suicide and 15.1% had a major depressive episode [8]. In Latin America, UNICEF mentions that the latest available estimates suggest that 15 per cent of children and adolescents aged 10-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean, around 16 million, live with a diagnosed mental disorder [44]. This problem, which is not foreign to the American continent, leads to the need to carry out research in this population that promotes strategies such as exercise and physical activity to determine their impact. At the same time, it is important to carry out research in languages such as Spanish or Portuguese, which will allow a greater approach to the scientific community.

It should be noted that our study included a representative population sample with a total of 85,572 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 16, in which the studies of Wassenaar et al. [38] and Zhang et al. [42], contributed the largest number of participants with 16,017 and 67,281 participants, respectively. Similarly, the studies showed a representative sample for each sex, being 50.33% men. In relation to BMI, it was observed in the study of Ho et al. [40] 22% of the experimental group and 20.4% of the control group were overweight. Meanwhile, Zhang et al. [42] reported a 12.3% of overweight population. Kokka et al. [45], in its research entitled Psychiatric Disorders and Obesity in Childhood and Adolescence-A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies, mention that the obesity and psychiatric disorders have high prevalence and are both considered major health problems. Also, reported as a result of its research a significant relationship between the psychiatric disorder and obesity. These findings justify the need to apply specific interventions such as physical exercise, which has proven to be a strategy for weight reduction and is also an important factor in maintaining adequate mental health in the adolescent population [46],

The study by Åvitsland et al. [47], carried out in Norwegian adolescents, whose objective was to evaluate body composition, muscular strength, cardiorespiratory fitness and their relationship with mental health, also found, like our study, positive results in relation to the effects of exercise on physical qualities and mental health. An association was observed between cardiorespiratory fitness and levels of psychological difficulties in adolescents. The results of this study support that moderate to HIIT in adolescents increases aerobic fitness capacity and may be more conducive to the maintenance of mental health. This is consistent with the study by Mendonça et al. [48], where they found that using moderate and high intensity continuous training with resistance training had a positive effect for health-related physical fitness components in adolescents. As well as the study by Leahy et al [49] where they realized a review of HIIT for cognitive and mental health in youth between 5 and 18 years old, they found that HIIT can improve cognitive function and mental health in children and adolescents.

In our study the types of training mentioned were PPE + habitual activities, AEP, HIIT = gross motor cardiorespiratory exercises, EEP, HIIT= combination of cardiorespiratory resistance and body weight exercises with high intensity, 1 session per day 3 times per week for 8 weeks and 10 minutes per session. Romero et al. [50] conducted a study with children with obesity, based their exercise prescription for 20 consecutive weeks with 2 weekly sessions with a duration per session of 50 min. It should be noted that according to the characteristics and goals set for each individual, the exercise prescription is made on an individual basis.

In our research, it was shown that VPA and HIIT have a positive impact on the mental health of this population, with increased quality of life, decreased mental disorders, stress, anxiety and improvements in the perception of appearance. In addition, they increase aerobic capacity and muscle strength [51]. Dahlstrand et al. [52] carried out a comparison between different types of training which included light, vigorous and very vigorous physical activity, where it was concluded that vigorous physical activity was the best associated with health indicators in terms of mental health. Chmelík et al. [53] exposed that there is a positive and significant association between mental health and vigorous physical activity in adolescents based on a deeper awareness of the association between physical activity and satisfaction with quality of life.

Finally, statistical significance was found in three of the articles included in our study, Ho et al. [40] in the mental component score and psychological assets (Self-efficacy and resilience), Eather et al. [41], in the physical self-concept test, and Bell et al. [43] for the SDQ subscale, assessment of behavioral problems, and hyperactivity. However, as a limitation of the present study, it was found that there is no standardized instrument for measuring mental health in adolescents, which hindered the comparative analysis between variables. According to the study by Orth et al. [54] titled Measuring Mental Wellness of Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Instruments, the review concludes that there is a lack of consensus in the development of instruments for adolescents that measure mental health, many of these instruments are in English and come from developed countries. This leads to a need for a conceptualized and operationalized instrument for adolescents in different contexts.

Limitations

We found that there is a deficiency in the accuracy of studies to describe exercise prescription parameters in greater detail, which include all parameters. A more detailed description would facilitate comparative analysis and would allow providing recommendations with greater specificity for implementation. It was also found that the scales used to assess mental health were different in each of the articles found, which made it difficult to carry out a comparative analysis between them.

As a projection in future research, it is suggested to continue strengthening the scientific evidence regarding the implementation of mental health assessment scales in structured physical exercise programs.

Conclusions

According to the evidence collected physical exercise such as PPE, HIIT and VPA improves mental health in adolescents. Its implementation should be based on the parameters of exercise prescription: intensity, volume, progression, frequency and type of exercise. Moderate to high intensity aerobic exercise programs are most beneficial in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, improving self-esteem, quality of life, and body perception.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2024. Mental health; 2022 Jun 17 [cited 2024/03/05]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

2. World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2024. Mental health of adolescents; 2021 Nov 17 [cited 2024/03/05]; [about 5 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

3. Patel AK, Bryant B. Separation Anxiety Disorder. JAMA [Internet]. 2021;326(18):1880-. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.17269

4. Unicef [Internet]. Nueva York: Unicef: c2024. Unicef for every child. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the situation of every children and woman. Mental health; 2024 Jun [cited 2024/03/05]; [about 14 screens]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/mental-health/

5. Hajek A, Neumann-Böhme S, Sabat I, Torbica A, Schreyögg J, Barros PP, et al. Depression and anxiety in later COVID-19 waves across Europe: New evidence from the European Covid Survey (ECOS). Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2022;317:114902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114902

6. 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2022 Oct. CHILD AND ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587174/

7. Brannen DE, Wynn S, Shuster J, Howell M. Pandemic Isolation and Mental Health Among Children. Disaster Med Public Health Prep [Internet]. 2023;17:e353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2023.7

8. Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichtstein J, Black LI, Everett Jones S, Danielson ML, et al. Mental health surveillance among children - United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Suppl 2022;71(Suppl-2):1-42. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

9. Hossain MM, Nesa F, Das J, Aggad R, Tasnim S, Bairwa M, et al. Global burden of mental health problems among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2022;317:114814. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114814

10. Huang Y, Li L, Gan Y, Wang C, Jiang H, Cao S, Lu Z. Sedentary behaviors and risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Transl Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020;10(1):26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0715-z

11. Andermo S, Hallgren M, Nguyen T-T-D, Jonsson S, Petersen S, Friberg M, et al. School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open [Internet]. 2020;6(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-00254-x

12. World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2024. Physical activity; 2024 Jun 26. [cited 2024/03/05]; [about 5 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

13. Cooper HK, Blair SN. Exercise physical fitness [Internet]. Encyclopedia Britannica; 2024 Jul 26 [updated 2024 Jul 26; cited 2024/04/05]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/exercise-physical-fitness

14. Borge S. What is Sport? Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 2021;15(3):308-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2020.1760922

15. Mannello M, Casey T, Atkinson C. Article 31: Play, Leisure, and Recreation. In: Nastasi BK, Hart SN, Naser SC, editors. International Handbook on Child Rights and School Psychology [Internet]. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 337-48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37119-7_21

16. Kliziene I, Cizauskas G, Sipaviciene S, Aleksandraviciene R, Zaicenkoviene K. Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021;18(14):1-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147536

17. Ekeland E, Heian F, Hagen KB, Abbott JM, Nordheim L. Exercise to improve self-esteem in children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2004;(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003683.pub2

18. Jia N, Zhang X, Wang X, Dong X, Zhou Y, Ding M. The effects of diverse exercise on cognition and mental health of children aged 5-6 years: A controlled trial. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2021;12:759351. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759351

19. Pascoe M, Bailey AP, Craike M, Carter T, Patten R, Stepto N, et al. Physical activity and exercise in youth mental health promotion: a scoping review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med [Internet]. 2020;6(1):e000677. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000677

20. Zhang G, Feng W, Zhao L, Li T. The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2024;14(1):5488. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56149-4

21. JBI Global Wiki [Internet]. JBI; c2024. Appendix 10.2 PRISMA ScR Extension Fillable Checklist; 2024 Mar 26 [cited 2024/05/03]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355863360/Appendix+10.2+PRISMA+ScR+Extension+Fillable+Checklist

22. Smart NA, Waldron M, Ismail H, Giallauria F, Vigorito C, Cornelissen V, et al. Validation of a new tool for the assessment of study quality and reporting in exercise training studies. TESTEX. Int J Evid Based Healthc [Internet]. 2015;13(1):9-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000020

23. Sjøgaard G, Søgaard K, Hansen AF, Østergaard AS, Teljigovic S, Dalager T. Exercise Prescription for the Work-Life Population and Beyond. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol [Internet]. 2023;8(2):1-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk8020073

24. Marcotte-Chénard A, Little JP. Towards optimizing exercise prescription for type 2 diabetes: modulating exercise parameters to strategically improve glucose control. Translational Exercise Biomedicine [Internet]. 2024;1(1):71-88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/teb-2024-2007

25. Sánchez Milá Z, Villa Muñoz T, Ferreira Sánchez MDR, Frutos Llanes R, Barragán Casas JM, Rodríguez Sanz D, et al. Therapeutic Exercise Parameters, Considerations and Recommendations for the Treatment of Non-Specific Low Back Pain: International DELPHI Study. J Pers Med [Internet]. 2023;13(10):1-23. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101510

26. Arora NK, Donath L, Owen PJ, Miller CT, Saueressig T, Winter F, et al. The Impact of Exercise Prescription Variables on Intervention Outcomes in Musculoskeletal Pain: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Sports Med [Internet]. 2024;54(3):711-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01966-2

27. Rooney D, Gilmartin E, Heron N. Prescribing exercise and physical activity to treat and manage health conditions. Ulster Med J [Internet]. 2023;92(1):9-15. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9899030/

28. Loellgen H, Zupet P, Bachl N, Debruyne A. Physical Activity, Exercise Prescription for Health and Home-Based Rehabilitation. Sustainability [Internet] 2020;12(24):1-12. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su122410230

29. Stassen G, Baulig L, Müller O, Schaller A. Attention to Progression Principles and Variables of Exercise Prescription in Workplace-Related Resistance Training Interventions: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2022;10:832523. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.832523

30. Lucini D, Pagani M. Exercise Prescription to Foster Health and Well-Being: A Behavioral Approach to Transform Barriers into Opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021;18(3):1-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030968

31. McLeod JC, Currier BS, Lowisz CV, Phillips SM. The influence of resistance exercise training prescription variables on skeletal muscle mass, strength, and physical function in healthy adults: An umbrella review. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2023;13(1):47-60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2023.06.005

32. Veneman T, Koopman FS, Daams J, Nollet F, Voorn EL. Measurement Properties of Aerobic Capacity Measures in Neuromuscular Diseases: A Systematic Review. JRM [Internet]. 2022;54:1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v54.547

33. Bal PM, Izak M. Paradigms of Flexibility: A Systematic Review of Research on Workplace Flexibility. European Management Review [Internet]. 2021;18(1):37-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12423

34. Li B, Sun L, Yu Y, Xin H, Zhang H, Liu J, et al. Associations between body composition and physical fitness among Chinese medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2022;22(1):2041. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14548-0

35. Wren-Lewis S, Alexandrova A. Mental Health Without Well-being. J Med Philos [Internet]. 2021;46(6):684-703. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhab032

36. Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ [Internet]. 2020;368:l6890. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890

37. Costigan SA, Eather N, Plotnikoff RC, Hillman CH, Lubans DR. High-Intensity Interval Training for Cognitive and Mental Health in Adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2016;48(10):1985-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000993

38. Wassenaar TM, Wheatley CM, Beale N, Nichols T, Salvan P, Meaney A, et al. The effect of a one-year vigorous physical activity intervention on fitness, cognitive performance and mental health in young adolescents: the Fit to Study cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2021;18(1):47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01113-y

39. Frömel K, Šafář M, Jakubec L, Groffik D, Žatka R. Academic Stress and Physical Activity in Adolescents. Biomed Res Int [Internet]. 2020:4696592. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4696592

40. Ho FKW, Louie LHT, Wong WH, Chan KL, Tiwari A, Chow CB, et al. A Sports-Based Youth Development Program, Teen Mental Health, and Physical Fitness: An RCT. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2017;140(4). doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1543

41. Eather N, Morgan PJ, Lubans DR. Effects of exercise on mental health outcomes in adolescents: Findings from the CrossFit™ teens randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Sport and Exercise [Internet]. 2016;26:14-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.05.008

42. Zhang X, Jiang C, Zhang X, Chi X. Muscle-strengthening exercise and positive mental health in children and adolescents: An urban survey study. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2022;13. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.933877

43. Bell SL, Audrey S, Gunnell D, Cooper A, Campbell R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2019;16(1):138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7

44. UNICEF [Internet]. New York: UNICEF; c2024. Over US$30 billion is lost to economies in Latin America and the Caribbean each year due to youth mental health disorders; 2021 Oct 5 [cited 2024/05/26]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/press-releases/over-us30-billion-is-lost-to-economies-in-latin-america-and-caribbean-each-year-due-youth-mental-health-disorders

45. Kokka I, Mourikis I, Bacopoulou F. Psychiatric Disorders and Obesity in Childhood and Adolescence-A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies. Children [Internet]. 2023;10(2):1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020285

46. Bülbül S. Exercise in the treatment of childhood obesity. Turk Arch Pediatr [Internet]. 2020;55(1):2-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.14744/TurkPediatriArs.2019.60430

47. Åvitsland A, Leibinger E, Haugen T, Lerum Ø, Solberg RB, Kolle E, et al. The association between physical fitness and mental health in Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020;20(1):776. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08936-7

48. Mendonça FR, Ferreira de Faria W, Marcio da Silva J, Massuto RB, Castilho Dos Santos G, Correa RC, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise combined with resistance training on health-related physical fitness in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. J Exerc Sci Fit [Internet]. 2022;20(2):182-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2022.03.002

49. Leahy AA, Mavilidi MF, Smith JJ, Hillman CH, Eather N, Barker D, et al. Review of High-Intensity Interval Training for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2020;52(10):2224-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002359

50. Romero-Pérez EM, González-Bernal JJ, Soto-Cámara R, González-Santos J, Tánori-Tapia JM, Rodríguez-Fernández P, et al. Influence of a physical exercise program in the anxiety and depression in children with obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020;17(13):1-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134655

51. Marsigliante S, Gómez-López M, Muscella A. Effects on Children's Physical and Mental Well-Being of a Physical-Activity-Based School Intervention Program: A Randomized Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2023;20(3):1-16. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031927

52. Dahlstrand J, Fridolfsson J, Arvidsson D, Börjesson M, Friberg P, Chen Y. Move for Your Heart, Break a Sweat for Your Mind: Providing Precision in Adolescent Health and Physical Activity Behaviour Pattern. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2023;73(1):29-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.03.006

53. Chmelík F, Frömel K, Groffik D, Mitáš J. Physical activity and life satisfaction among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychol [Internet]. 2023;241:104081. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.104081

54. Orth Z, Moosajee F, Van Wyk B. Measuring Mental Wellness of Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Instruments. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2022;13:835601. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835601