Social Stigma of Overweight and Obesity in Primary School Children: A Systematic Review

Estigma social del sobrepeso y obesidad en niños de escuela primaria: una revisión sistemática

Sara Concepción Maury Mena , Lucia Lomba Portela, Juan Carlos Marín Escobar, Olman Salazar Ureña, Luz Marina Alonso Palacio, Vanessa Navarro Angarita, Rosely Rojas Rizzo

Abstract

Introduction: The World Health Organization established in 2016 that there are more than 43 million overweight and obese children in the world, being one of the most serious public health problems, which affects the physical health of children and brings psychosocial consequences such as social stigma in the school and its social environment.

Objective: Conduct a systematic review of social stigma in overweight and obese children in primary education to design appropriate interventions and prevention programs.

Materials and methods: Systematic review in the PubMed/Medline, ERIC and Google Scholar databases.

Results: Of 1709 scientific articles, 407 were reviewed in full text and 39 were included when meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria. There are significant differences between boys and girls; social stigmatization affects girls more, due to the internalization of beauty and body image canons based on thinness. An association was found between academic performance and bullying, self-stigma, and social stigma.

Conclusion: Overweight/obese children are more likely to be stigmatized, to be bullied physically rather than relationally, and to be bullied and victimized by their normal weight peers. The acquired stigma derives from a socioculturally penalized image that has consequences on the psychological development of children who are forming their personality and values. It is necessary to propose specific preventive interventions in the school environment to face the consequences of social stigma and improve the development of body image.

Keywords

Childhood overweight and obesity; social stigma; primary education; prevention; intervention; systematic review.

Resumen

Introducción: La Organización Mundial de la Salud estableció en el 2016 que hay más de 43 millones de niños con sobrepeso y obesidad en el mundo, siendo uno de los problemas de salud pública más graves, el cual afecta la salud física de los niños y trae consecuencias psicosociales, como el estigma social en la escuela y su entorno social.

Objetivo: fue realizar una revisión sistemática del estigma social en niños con sobrepeso y obesidad en la educación primaria, para diseñar intervenciones y programas de prevención apropiadas.

Métodos: Revisión sistemática en las bases de datos PubMed/Medline, ERIC y Google Académico (Scholar).

Resultados: De 1709 artículos científicos, se revisaron 407 en texto completo y 31 fueron incluidos al cumplir con los criterios de inclusión/exclusión. Existen diferencias significativas entre niños y niñas; la estigmatización social afecta más a las niñas debido a la internalización de cánones de belleza e imagen corporal basados en la delgadez. Se encontró asociación entre el rendimiento académico y el acoso escolar, el autoestigma y el estigma social.

Conclusión: Los niños con sobrepeso/obesidad tienen mayores probabilidades de ser estigmatizados, de que el acoso sea físico más que relacional y de intimidación y victimización por parte de sus iguales con normopeso. El estigma adquirido se deriva de una imagen penalizada socioculturalmente, que trae consecuencias en el desarrollo psicológico de los niños que están formando su personalidad y sus valores. Es necesario proponer intervenciones preventivas específicas en el ámbito escolar para afrontar las consecuencias del estigma social y mejorar el desarrollo de la imagen corporal.

Palabras clave

Sobrepeso y obesidad infantil; estigma social; educación primaria; prevención; intervención; revisión sistemática.

Introduction

The global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has increased from less than 1% in 1975 (11 million) to almost 14% (124 million) in 2016 [1,2], representing one of the most serious health problems, with features of pandemic, of the 21st century. These figures continue to rise at a worrying rate, especially in developing countries such as Colombia. The problem lies, above all, in the fact that overweight and obese children maintain this trend in adulthood, which increases the chances of developing, at an early age, Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions [2].

Evidence [3-8] shows that the increased prevalence of NCDs is associated with unhealthy lifestyles, characterized by sedentarism, inadequate diet, the daily use of information and communication technologies that keep users inactive and the habits acquired since childhood that are maintained into adulthood.

Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents have been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as follows:

Overweight is equal to the Body Mass Index (BMI) for age and gender added up to more than one standard deviation above the median established in infant growth patterns, and obesity is equal to BMI for age and gender plus more than two typical deviations above the median established in infant growth patterns [2 p4].

Today, many children grow up in an obesogenic environment that comes to favor and encourage weight gain, mostly because of the availability, affordability and commercialization of unhealthy foods and low energy consumption due to lack of physical activity and sedentary lifestyle, as the time children spend in front of a screen has increased [9,10].

A child’s biological and psychosocial responses to an obesogenic environment may be affected by socio-cultural determinants prior to birth, increasing, as a matter of course, the numbers of obese children. It is therefore necessary to change unhealthy dietary patterns and increase physical activity, while these socio-cultural determinants must be modified [11,12].

Fortunately, the conditions of overweight and obesity are largely reversible, so prevention work is needed that includes education in healthy lifestyles, increase and incentive of physical activity in all school-age children and teaching them proper eating habits. It is also necessary to choose healthy foods for infants and children under the age of five, as it is known that food preferences are established from an early age in the life cycle [2,13].

Lack of education and knowledge about adequate and balanced nutrition, added to the difficulties in the availability and accessibility of healthy food and the promotion, in mass advertisements, of unhealthy drinks and food for children and families contribute to aggravate this problem. In the conditions of globalization, digitization and urbanization that the world is living today, there are few possibilities for physical activity, that would allow the energy expenditure necessary to have an adequate weight [2,3,6].

In Latin America, the prevalence of overweight and obesity also shows figures that reflect the severity of the situation. In 2014, this prevalence was 7.1% in children under 5 years of age. In children between the ages of 5 and 12, it reached standards between 18.9% and 36.9% and, in adolescents, it was 16.6%-35.8%; that is, from 20% to 25% of the total population of children and adolescents in Latin America suffers from overweight and obesity [14].

Mexico ranks first worldwide in childhood obesity (26% for both genders, 4.1 million children between 5 and 12 years) and is second in obesity in adults (the first place belongs to the United States) [15,16]. In Colombia, according to the Third National Survey of the Nutritional Situation [17], the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 24.4% in children between 5 and 12 years of age, the problem being more serious among the population with better socioeconomic situation.

Excess weight in childhood and adolescence represents physiological and biomedical problems and psychosocial consequences and risk factors, such as depression, lower self-esteem, bullying by peers, difficulties in socialization, being associated with negative stereotypes and the development of stigmatizing prejudices and discrimination in the social environment [18-23].

The stigmatization of overweight or obese children and adolescents has been recognized in Western cultures and can range from verbal jokes, such as insults, derogatory comments and mockery, to physical harassment, reflected in blows, kicks or shoves, which, spread over time, can lead to victimization and discrimination. This can result in social exclusion, being ignored or avoided, or becoming the target of rumors, because stigma can arise in subtle ways or manifest itself openly [24], and seems to have increased in today’s society [18-19,24-25].

Stigma is defined as a deeply discrediting attribute, mark or characteristic (real or supposed), usually based on a physical difference or deviation from the social norm, such as a physical deformity, character flaws or aspects related to family history [20,21,26-28], which penalizes the person in his or her social status.

For Goffman [29], there is nothing in the attribute itself that makes it stigmatizing, because an attribute is neither honorable (positive) nor ignominious (negative). What is important is the meaning that the social environment gives to this attribute, by linking it with negative stereotypes. Therefore, stigma is a social construct [22,29,30], a conjunction between the mark, attribute or characteristic and the social stereotypes associated with these, which create a socially devaluative identity, which leads to the loss of status of those who possess it [30].

As for overweight and obesity, Ozuna et al. [19] define stigma as the rejection and social denigration suffered by people who do not meet the prevailing social standards regarding weight and body shape and image, producing negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination. This of course generates psychosocial affections of great consideration, which add to the health problems that these patients already suffer [19,22,25,31].

Holzemer et al. [32] identified three types of stigma: stigma received, stigma by association and self-stigma, which is the result of internalizing stigmatizing behaviours observed in the community and may relate to other types of stigma and prejudice present in society, such as those associated with ethnicity, economic income, social classes or gender, among others [31-33].

Prejudice, stereotypes, stigma and discrimination are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. It could be said that stigma is the basis of discriminatory actions and behaviour (staging of stigma) and, in turn, is the product of prejudice and stereotypes, that generate actions or omissions in people that harm or deny services or rights to victims [34-39].

On the other hand, it is also important to consider the frustrations with the difficulties of adherence to treatment when a treatment is followed and weight loss is not achieved, and the psychopathological consequences of trying to sustain a diet (effective or not). Children and adolescents in this situation often feel guilty and ashamed and are criticized for their "failure" by their family members, peers and health professionals [8].

Given this scenario, some large-scale efforts have been generated to provide health interventions in areas such as effective nutrition and physical activity, aimed at children and because the school represents the ideal environment for a more rational and rapid strategy that will lead to a greater coverage of this population [40-42]. Evidence [3-8] is currently available to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of educational interventions that are sustainable if regularly integrated into the school curriculum [6].

In countries such as Colombia, there is a normative and political framework that favors the feasibility of such interventions and makes them enforceable (Article 12 of Law 115 of 1994, 2006; Law 1355 of 2009; Law 2120 of 2021), because they advocate training for comprehensive prevention, the promotion and preservation of health and body hygiene, physical education/activity, recreation, sport and adequate use of leisure time, and the promotion of healthy eating environments.

For these reasons, the “Program Generación Vida Nueva" (PGVN) [8] emerged in 2015 as a strategy in the District of Barranquilla, Colombia, to address obesity and overweight in children from 5 to 12 years in the school environment and to promote healthy lifestyles. The PGVN aims to create interventions integrated with the daily educational practice of the 17 participating primary schools (10,000 students) and has developed annual anthropometric activities [43], including the measurement of the Body Mass Index (BMI) and medical checks of overweight or obese children.

By carrying out anthropometric measurements that confirm overweight or obesity, these children have felt discriminated against by their peers and feel different when invited to follow-up and medical, nutritional, physical activity and psychosocial interventions, necessary for their condition. Parents have also said that their sons and daughters bring home this sense of social stigma and have communicated it to schools. Teachers have also noticed the discomfort of these children during classes.

However, at least from this context, there are no known research approaches or studies that show the reality of stigmatization and stereotypes that overweight and obese children are subjected to. The PGVN’s work has shown very accurately the prevalence and comorbidities of this problem, but the psychosocial dimensions are just a reference. In fact, there is little work on stigmatization in Colombia and Latin America.

As a way of approaching this reality, it is proposed to carry out a systematic review that allows knowing the state of research regarding the levels of stigma and discrimination of overweight and obese children in the context of primary schools. The fundamental purposes of this work are two: First, to assist in the planning of research of a quasi-experimental or experimental nature that sensitizes the academic community to the incidence of stigmatization on the mental health of individuals and specifically children; second, appropriate theoretical and practical elements for the design of accompanying and intervention strategies, which will make it possible to face this reality, suffered by many children and adolescents, and thus prevent the emergence of NCDs, such as diabetes, in early stages of their development.

Several hypotheses accompany this systematic review. The first is that overweight and obese children do suffer to some extent from stigmatizations, many of which occur in the educational systems they are part of and are generated by classmates, but also by teachers themselves. The second hypothesis is that the stigmatization suffered by these children has different levels: there is social stigmatization, which is when it comes from some of their peers; institutional stigmatization, the derivative of schools; self-stigmatization, which is that stigma that the same child infringes himself or herself, that is, "As I am fat, then I am clumsy". Finally, one last hypothesis is that stigmatization and its effects can be reduced through educational strategies that can be established within curricular or extracurricular processes.

As a further goal, the research team aims to conduct meta-analytic studies to determine the effects of overweight and obesity in children and youth population in a variety of psychosocial dimensions, including self-concept, self-esteem, learned helplessness, self-discrimination, supported, of course, by statisticians used from controlled studies of the cause-effect type. However, the current state of research, in these subjects, did not allow finding evidence of such studies with sufficient statistical strength to consolidate a meta-analysis.

Methods

Study design

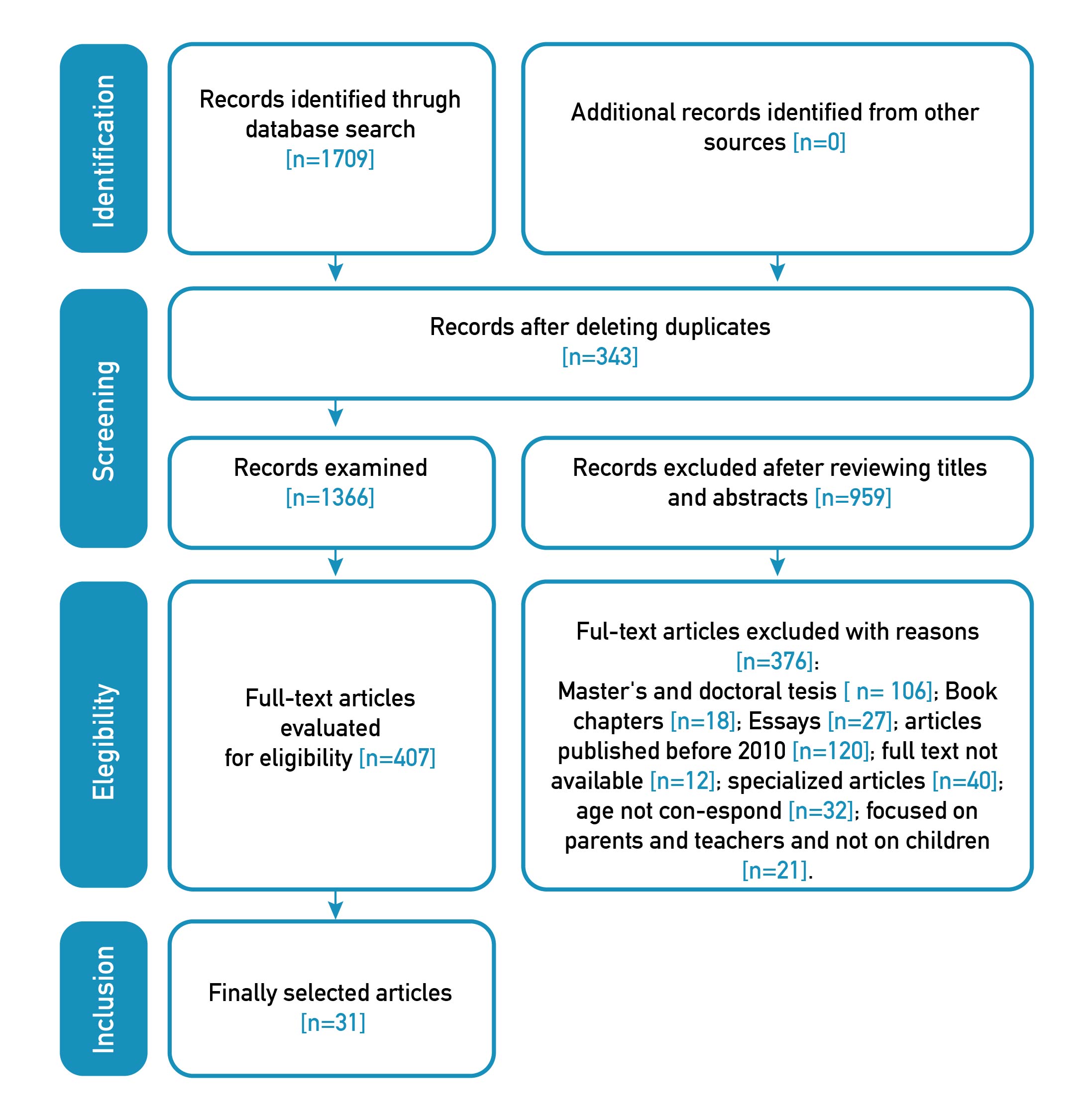

The research design corresponds to a systematic review, defined by the Cochrane Manual [44] as the gathering of all empirical evidence according to clearly established inclusion and exclusion criteria to answer precise research questions, using systematic and reliable methods to minimize bias, to draw useful conclusions for decision-making. The design followed the PRISMA methodology reflected in Figure 1 [44].

Figure 1. Study search results

Inclusion criteria

All types of primary and secondary research were included, with populations of children and adolescents between 5 and 13 years, studying the characteristics of social stigma associated with the condition of overweight or obesity (measured by the BMI, by questionnaires or by observation) in the context of primary schools and the effects of discrimination, mockery, social stigma, ideal body image and explicit or implicit attitudes towards children’s weight, in addition to studies published in English and/or Spanish by peer-reviewed indexed journals, between 01-01-2010 and 31-03-2021.

Exclusion criteria

Studies with populations that did not meet the given age range, those not conducted in the context of primary schools, added to investigations published before 2010 and after March 2021, as well as those published in languages other than English and Spanish were excluded.

Sources of information

A search was conducted in the Pub Med/Medline, ERIC and Google Scholar databases. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined, searches were performed with keywords, the descriptors that were selected in DeCS/MeSH, the search equations with Boolean connectors and the filters described in Table 1. The articles were searched in English and Spanish. The selection process of the studies was carried out by two researchers independently and, when they did not come to an agreement, a third researcher intervened to achieve the final selection.

Table 1. Descriptors and search equations in databases.

| Database | Descriptors | Search equations | Filters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pub Med/Medline | Social stigma, Obesity, Children | ((social stigma) AND (obesity)) AND (children) | Last 10 years, from 2010 to 2020, English-Spanish |

| ERIC (Proquest UNIR) | Social stigma, Obesity, Elementary School | MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Stereotypes") OR (social stigma) OR discrimination AND (fat prejudice) AND MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Obesity") AND MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Elementary School Students") | Scientific journals, 2010-01-01 to 2020-12-31, Elementary Education |

| Google Scholar (in English) | overweight, obesity, elementary school children prevention, intervention, social stigma, stigmatization, discrimination, prejudice, stereotype | Overweight, obesity, elementary school, children, prevention, social intervention, stigma, stigmatization, discrimination, prejudice, stereotype. | 2010-2020, Where words appear throughout the article |

| Google Académico (Google Scholar in Spanish) | Sobrepeso, obesidad, escuela primaria, estigma social, estigmatización, discriminación, prejuicio, estereotipo | Sobrepeso, obesidad, escuela primaria, estigma social, estigmatización, discriminación, prejuicio, estereotipo. | 2010-2020. |

Selection of studies, extraction and analysis of data

The studies were coded and classified with a data extraction form according to first author, year of publication, type of study, population, average age, social extraction of the sample, school grade, country of study and results found. An analysis was made of the scope, nature and distribution of the studies included in the review, as well as the content of the data collected; the literature was summarized according to psychosocial risk factors found, and, the results of the studies were classified into categories and subcategories when necessary. Duplicates were eliminated, titles and abstracts and full texts were examined and the studies to be included were defined. A description of the analysis categories found was made and is presented in the Results section.

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies

The evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies was carried out by two researchers, following the criteria of the NewCastle-Ottawa scale of 2010 [45]. When these two researchers disagreed, a third researcher intervened.

Ethical considerations of the research

As this is a systematic review, there is no need for informed consent, nor to apply for permits because a population was not directly affected.

Results

The search in the PubMed/Medline, ERIC, Google Scholar (in English and Spanish) databases yielded 1709 articles. After eliminating duplicates and excluding by titles, there were 407 articles with which summaries and complete articles were read to verify the inclusion criteria. Then, 376 studies were excluded for the reasons described in Figure 1 and 31 articles were included in the study.

The 31 studies covered a population of 24935 children, of whom 49.67 per cent were girls and 50.33 per cent were boys. The mean age ranged from 7.5 to 11.9 years. There was little information, in the studies, on the social extraction of the sample and some did not report on the school grades attended by the children, although these were generally primary school grades. Most of the studies were of a cross-sectional type (14/31), followed by longitudinal studies of a prospective type (5/31) and studies of a correlative type (5/31). We found 3 Randomized Clinical Trials, 1 qualitative study, 1 mixed study (qualitative-quantitative) and 1 inter and intra-subject experimental study. Details and summaries of the results of the included studies are available in the Appendix.

Most of the research was done in the United States (10/31), 3 in Ireland, 3 in Germany, 2 in Spain and 1 in countries such as Italy, Canada, Greece, Hungary, Australia, China and Cuba. The journals that have published such studies mostly belong to the area of health (especially pediatric or obesity; 30/31) and only 1 to the area of education.

Characteristics of social stigma for overweight and obesity in school-age children

Most of the studies (96%) included in this review (30/31) provided information on the characteristics of social stigma for overweight and obesity in school-age children. In terms of content analysis, it was found that children, during primary education, are able to stigmatize their peers and show their favoritism towards certain peers [46]. Overweight and obesity are highly stigmatized conditions in Western society and the message is conveyed, especially to children and women, that thinness means power, success, beauty and self-efficacy [47].

It is for this reason that overweight or obese children are more likely to be stigmatized in an individual or social context compared to their normal weight peers [46-59], which is why they also suffer from bullying [54].

The social stigma of overweight and obesity is frequent and its prevalence among certain age groups and populations, such as school-age children, makes this population more vulnerable [45,56]. Bullying resulting from this stigma affects the well-being, quality of life and academic performance of overweight or obese children in primary school, and the consequences may be lifelong [54].

The levels of evidence of the studies are low (only 1 study was an ACE), so statistics and effect sizes could not be presented, and the variables measured were described, which were mostly performed in a qualitative way.

Weight labelling

29% of the studies included in this review worked with the weight labeling variable. According to the longitudinal study conducted by Hunger and Tomiyama [59], in which anthropometric and weight labelling measurements were made, 57.9% of the participants reported being labeled "fat". Baseline BMI and labeling condition correlated moderately with this result (r = 0.41, P = less than 0.001). In the evaluation of this association 10 years later, labeling remained a significant predictor of overweight or obesity with an OR = 1.66. The OR was 1.62 when it was family members who labeled and 1.40 when it came to other people.

Mustillo et al. [60] found a link between psychological distress experienced from 18 to 21 years and parental and peer labeling due to the stigma of obesity from 9 to 10 years old, especially in white children.

On the other hand, implicit and explicit attitudes associated with negative attitudes towards overweight or obese children are quite widespread and have been shown to be resistant to interventions. These weight-related attitudes were studied in the cross-sectional research of Hutchinson and Mueller [61], where findings indicate that implicit and explicit attitudes towards overweight and obesity are significantly correlated. It was also found that implicit attitudes associated with weight tended to be higher in older children.

Social stigma of overweight and obesity and school harassment

About 23% of the included studies treated school harassment among their variables. For example, the cross-sectional study by Lumeng et al. [52] investigated the relationship between social stigma and harassment as reported by the child, the child’s mother and the teacher. It was noted that 33.9 per cent (teacher’s report), 44.5 per cent (mother’s report) and 24.9 per cent (child’s report) of children had been harassed. We found a significant independent relationship between being obese or overweight and being harassed with a probability ratio of 1.63, 95% CI, 1.18-2.25, after adjusting it according to school grade, gender, race and family income.

On the other hand, the research by Madowitz et al. [62], which performed logistic and linear regressions to evaluate the relationship between the variables of harassment, depression and unhealthy weight control behaviors, found that overweight or obese children who are bullied have significantly higher levels of depression (B=6.1; SE=2.3) and are 5 times more likely to have unhealthy weight management behaviors (OR=5.1, 95% CI, 1.5-17.4) and that teasing associated with excess weight is related with negative psychosocial factors in these children.

The only Latin American study that was part of this review [63], conducted in several municipalities in Cuba, found that Cuban schoolchildren do not accept their overweight or obese peers contextually. In Cuba, obese children are stigmatized to a lesser degree than in America or New Zealand (where the same type of study was conducted), but stigmatization does occur anyway. Children of both genders with little control over their eating habits suffer the greatest consequences of bullying and peer rejection.

Social stigma of overweight and obesity on the part of peers

About half of the studies (48%, 15/31) considered the social stigmatization of overweight and obesity by peers. Regarding the perception of obesity by children and adolescents, in the qualitative study by Amini et al., children of both sexes stated that they did not like overweight and obesity and described them as excess fat and body weight, overeating, devouring, a condition that makes people lazy, ugly and heavy [64]. For their part, obese children considered obesity as a disease or cause of other diseases such as cancer, a stunting; something that will give a short life, that means having deprivations, a barrier to exercise, be agile and for routine activities, for social activities such as public speaking and for progress in life. Overweight or obese children are perceived as objects of ridicule, who are easily angered by taunts, and, adults and peers, expect an obese child to work and try harder because he or she "is strong".

The study by Brixval et al. [51] found that overweight students (OR 1.75, CI 95%, 1.18 -2.61) or obese students (OR 1.98, CI 95%, 0.79-4.95) were more exposed to bullying than their normal weight peers. Likewise, a greater internalization of weight bias (not properly calculating one’s weight considering that one has less weight than real) was associated with more teasing and harassment by peers and lower self-esteem.

The prospective study of Gmeiner and Warschburger [57] found that a considerable weight of the child, the female sex, experiencing teasing, a significant dissatisfaction with own weight, giving great importance to the figure and appearances, high depression scores and low parental education, are predictors of an internalization of Weight bias (a form of self-stigma in which the individual applies negative weight-based stereotypes against him or herself and blames him or herself for his or her condition regardless of actual weight) [63-66].

Likewise, in the research conducted by Kornilaki [67], in which two characters were showed, one with positive qualities (thin figures) and the other with negative (obese figures), to measure weight bias, it was observed that actual body size affected the accuracy of perceived body size: while normal weight children accurately identified their physical proportions, most overweight or obese children tended to underestimate their own weight. However, it was also found that perceived weight accuracy improved with age.

In the cross-sectional study by Gigirey et al. [68], conducted in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, it was found that a rejection of peers who are overweight or obese is produced. In addition, Olsen’s research [55] found that 59% reported their peers teasing their weight and 49% reported that their parents did the same, and these taunts, in turn, are related to eating problems ("binge eating") for emotional reasons.

The longitudinal "Growing Up" study, conducted in Ireland [69], found that children with a BMI indicating overweight or obesity were significantly more likely to be victimized and discriminated against compared to normal weight children. Weight-based teasing was found to be correlated with an increase in weight gain of the victims (33%), compared with peers who did not report it [70] and these experiences can increase the risk of health problems, including weight gain and bullying.

The research by Olsen et al. [55] found that obese children were considered less often as "best friends" and had a lower rating in the level of acceptance by their peers. In addition, they were described by their classmates as more socially withdrawn, with less leadership, with more aggressive-disruptive behavior, less physically attractive, more sick, tired and absent, less athletic and their relationships were different from those of normal weight peers.

Papp and Túry’s research [71] found that there are cultural differences in attitudes towards obesity and that it is worth continuing to explore these differences. Likewise, the study by Bird et al. [72] found that there were improvements in girls' body satisfaction, in issues related to appearance, eating behaviors and knowledge of the subject of the intervention; besides that, there was a significant reduction of cultural appearance ideals. However, none of these changes remained in follow-up 3 months after the intervention.

Body image and social stigma of overweight and obesity

The body image variable was considered by a large percentage of the studies (78%). Brixval et al. [51] found that body image mediates the associations between weight status and exposure to harassment in both boys and girls. Likewise, the study by Damiano et al. [73] found that 34% of overweight or obese girls reported a moderate level of dietary restriction and that most girls were satisfied with their body image, although half of them showed an internalization of the ideal of the slim figure. In addition, exposure to mass media and social media and talk about appearance were found to be the strongest predictors of dietary restriction. It is necessary to consider that the precision about the own weight improves with age, that is, the more children grow, the more they calculate with greater precision their own weight, despite that this indicates overweight or obesity. However, it was also observed that more than half of overweight or obese children stigmatized fat figures or appearances as if they represented other children and not them.

Jendrzyca and Warschburger [74] conducted a study to explore the role of social weight stigma in body image dissatisfaction and its influence on eating behaviors and found that weight status predicted dissatisfaction with one’s own body image, while weight stigma did not have a direct effect on eating disorders.

According to the study by McCormack et al. [53], 40% of overweight or obese children reported that their peers mocked them and 36% that their relatives too did, resulting in lower body satisfaction among children subjected to teasing and harassment compared to children who were not bullied. Research by Reulbach et al. [70] concluded that body image is more associated with victimization, discrimination and bullying than with objective weight classification based on BMI.

In the randomized clinical trial conducted by Ross et al. [75], to measure the effectiveness of the "Y’s Girl" body image program, the results showed that the girls who received the intervention reported an improvement in body image and self-esteem. Therefore, children who grow up with cultural influences that denigrate overweight and favor thinness as an ideal body image, associate people with overweight or obesity, explicitly or implicitly, with a few negative characteristics that have nothing to do with weight [74].

Moreover, in their study, Guardabassi and Tomasetto [76] decided to investigate whether the threat of negative stereotype associated with excess weight influences working memory. Working memory was found to decrease as BMI increased, showing that the threat of the stereotype of being less intelligent because of overweight or obesity arises at early ages and can influence working memory performance.

Self-stigma of overweight and obesity

About 31% of the studies examined self-stigma. The study by Chan et al. [77] found that overweight and obese children have a higher level of self-stigma and this, in turn, was related to more mental health problems, that is, overweight or obesity condition and victimization interact to influence the ratings of kindness and negative emotions. Thus, the state of self-victimization of children influences the ratings of social attraction, kindness and negative emotions.

For example, Olsen et al. [55] found that overweight/obese children perceive themselves more negatively compared to their normal weight peers and that age, gender, race and perceived responsibility affect attitudes towards an overweight or obese companion. The study by Wong et al. [78] found that overweight or obese children develop weight-related self-stigma (p= 0.,003), and tend to have poor quality of life in relation to health, compared to normal weight children, which means that the experience of teasing and self-stigma is more important than the actual state of weight.

Differences between boys and girls

Seventy-nine per cent of the studies considered differences between boys and girls. Several studies [44,45,55,72] were found in which the social stigma of overweight and obesity occurs more frequently among girls than among boys. Also, some research [61,72] showed that the associations between weight status, stigmatization for excess weight, dissatisfaction with body image and eating behaviors present differences according to gender, that is, girls stigmatized obese or overweight peers less than boys.

Some aspects of the prevention of social stigma due to overweight and obesity in school-age children

Several studies found that children included as factors of obesity prevention physical exercise, decrease food consumption in general, increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables, abstain from eating foods rich in calories, limit the time to watch TV and sleep, eat a light dinner and a hearty lunch, visit a nutritionist or dietitian and have a strong will [62,72].

Discussion

The findings indicate that overweight and obese children are more likely to be victims of social stigma and harassment, although this is more physical than relational, and intimidation and victimization on the part of their normal weight peers [44,46-55]. There are several studies [79-80] which confirm the aforementioned, giving rise to psychosocial problems in both the short and the long term [81].

The Strauss study [80] showed that a decrease in self-esteem in overweight or obese children can result in loneliness, sadness, nervousness and depression, and can affect the school performance of these children [75,79,81,82]. Previous experiences (negative perceptions) with overweight or obese individuals or family members can affect children’s attitudes and are important if a negative psychosocial impact on them is to be reduced [67].

These children have problems with their own body image and there's a possibility that they develop eating disorders [82]. Being labeled as "too fat, dumb, dirty, ugly, sloppy, unreliable, lazy, and a liar" during the childhood years can lead to increased chances of presenting overweight or obesity a decade later [57] because it augments obesogenic stress that triggers negative coping behaviors such as overeating [81].

The child labeled as "fat" is affected in his or her identity and this determines his or her behaviors, producing negative feelings that, in turn, lead him or her to overeat, falling into a vicious circle difficult to overcome and presenting a greater risk of suffering isolation, taunts, intimidation, insults, to the point of physical and not just relational aggression [81].

It is necessary to recognize the importance of using anthropometric measurements, such as BMI, from very early ages, to identify overweight/obese children and propose effective interventions to prevent and treat their excess weight, including psychosocial factors, such as the social stigma of this condition [79,83], and to develop positive coping behaviors and education in healthy lifestyles.

On the other hand, the review by Bautista Diaz et al. [83] found that within the family and in the school, health services and work environments, overweight discrimination is promoted and accepted on a daily basis, and as if it were normal. Instead, these should be environments from which social support and understanding would be expected.

The internalization of attitudes of rejection towards obese or overweight people is established from very early ages, where the family environment influences in this direction, in addition to the school environment, through the relationship with peers. In Mexico, it has been found that almost 70% of school peers associated overweight or obesity with negative characteristics such as "bad, dumb, loose, clumsy, with lack of discipline" [83]. Tiggerman and Barrett [84] found that children between the ages of 7 and 13 rated overweight children as less attractive (94%), less popular (81%) and lazier (86%) than normal weight children.

Other studies have identified that the subject of Physical Education at the basic and secondary school levels represents an aversive situation for students with excess weight, who expect to be accepted and respected by peers and the group [68,83]. Prejudices and negative attitudes towards excess weight have also been found in teachers, especially in those of physical activity, who have the prejudice that this condition means lower skills and lower performance in students [70,83].

The stigma of overweight or obesity stems from a socio-culturally determined image that is accepted and fulfilled by members of society (that thinness is beauty and means success) and, consequently, individuals suffering from this condition are marked by different prejudices that lack rational foundations [18,23-25,31,54,81,82,84-89]. These beliefs and attitudes are acquired during childhood and, by not being questioned, in adulthood end up becoming prejudices and stereotypes.

The experiences of being mocked, discriminated against and harassed due to body image have consequences for the psychological development of children, since childhood is a period where personality and values are formed that will endure throughout life [82]. Overweight/obese people tend to feel guilty and responsible for their condition, considering that they caused it to themselves, having to fight against habits that prevail in society, such as fast-food consumption and sedentarism, but it is this same society that judges and punishes them [81,86].

In Latin America there are few studies on this subject and it is necessary to develop more research on this condition and its particularities, especially considering that Mexico ranks first in the world in overweight children and young people and that 20 to 25% of the total population of Latin American children and adolescents suffer from overweight and obesity [14]: to this extent, we must respond to this phenomenon.

The included studies were published in health journals (30/31) and not in journals around education, which is indicating that the subject needs to be developed from an educational point of view, since the school environment is a day-to-day environment, in which many children are experiencing social stigma and ridicule from their school peers because of their excess weight.

In Colombia, normative and political foundations have been proposed to address the problem. This can be verified by revising Law 2120 of 2021 [8,90]; but action is missing in schools, as well as the development of scientific evidence of the intervention and prevention of this problem.

Implications, limitations and prospective

Implications for practice

There are studies aimed at reducing bullying derived from the social stigma of overweight and obesity that have short-term effectiveness, but studies are needed to verify their effectiveness in the long term. The studies show significant differences according to gender, body image, self-stigma, socioeconomic level, age of the subjects evaluated, and even race. It is advisable to consider that the stigma associated with weight can change with the growth and cognitive development of children.

While interventions that include physical activity and healthy eating are abundantly supported by scientific evidence, research on psychosocial factors of the stigma of overweight and obesity are less common. It is necessary to do more research in this regard and define common standardized measures, in evaluating study results, so that they can be comparable to each other. More experimental studies are needed to test the size of the effect of this social stigma on bullying and what could be the possible moderating factors of this effect.

Limitations and prospective

Search terms on the topic should be expanded because there are many more related terms that provide necessary and complementary information to understand the phenomenon as "Victimization, prejudice, physical and relational harassment, bullying, stigmatization of weight, Internalization of Weight Bias, fat label, self-stigma, intimidation, ridicule, mockery". There are very few experimental studies on the subject. The review shows that there is a relationship between social stigma and different psychosocial consequences, such as stress, obesogenic stress, depression, difficulty in relationship with peers, poor academic performance, low self-esteem, low satisfaction with one’s own body image and self-stigma, among others. It was also found that there is a relationship between the condition of excess weight in childhood and the possibility of being obese in the future, so it is necessary to measure the effects of all these relationships to propose new interventions, improve existing ones and make programmes to prevent overweight and obesity during childhood and adolescence, which are effective in the short term, but also in the long term.

Conclusions

First, it is emphasized that the objectives of the study were met and that we were able to compare the hypotheses related in the introduction to the results obtained in the 31 articles included in the present review. The results indicate that overweight or obese children must be supported to fight against different barriers to lose weight, especially psychosocial and socio-cultural barriers, such as social stigma derived from the environment.

Overweight and obese children are more likely to be exposed to social stigma, harassment, intimidation and victimization by their normal weight peers. It was also noted that children are at risk of weight gain due to teasing, harassment and social stigma and their consequences, engaging in a vicious cycle that needs to be broken. Therefore, interventions are needed to address the consequences of bullying and improve the body image of overweight/obese children.

The study shows that it is necessary to propose interventions aimed at children with normal weight to teach them empathic behaviors and altruistic and prosocial conducts towards their overweight peers, in order to reduce, for the latter, a negative psychosocial impact which would lead, inter alia, to lower motivation to exercise, lack of emotional coping to decrease overeating, and even other effects such as poor academic performance, depression, low self-esteem, obesogenic stress, which weighs heavily on overweight or obese children.

Western society presents idealizations of thinness from a very early age that cause prejudice and discrimination towards overweight and obesity, this condition being associated with negative characteristics that do not even have to do with weight, generating a higher level of self-stigma and mental health problems.

The social stigma of overweight and obesity is prevalent and certain age groups and populations, such as school children, may be more vulnerable than others. Therefore, it is important to identify external factors, correlations, categories and moderators of this stigmatization to propose interventions that are effective in reducing the negative impact that this age group suffers.

The multicausal and multidimensional origin of obesity needs an analysis of responsibility from individuals, family and society in general, since apart from the physiological consequences, psychosocial consequences on self-concept, self-esteem, obesogenic stress and body image can lead to more dangerous results than biomedical comorbidities themselves. It is important to improve the well-being and quality of life of these children, who feel socially devalued, through psycho-educational interventions.

Health professionals and primary school teachers should train in non-stigmatizing approaches to overweight and obesity, learning unbiased language and using empathic counseling techniques, such as motivational interviews. In addition, family inclusion and participation should be considered to improve this environment as well.

Healthy lifestyle interventions that promote regular physical exercise, healthy and balanced nutrition and an education in values (altruistic and empathetic prosocial behaviors and positive coping), would help reduce the global indicators of childhood overweight and obesity, combating the psychosocial problems that arise from this condition. The mission of the school should not only be the provision of healthy food but education in healthy lifestyles, installed in early childhood, to be taken to adulthood.

Referencias

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS), Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). La obesidad entre niños y adolescentes se ha multiplicado por 10 en los cuatro últimos decenios [Internet]. Londres: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2017. Disponible en: https://tinyurl.com/yt9a3tur

2. Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Informe de la Comisión para acabar con la obesidad infantil [Internet]. OMS; 2016. 42 p. Informe A69/8 24 mar 2016. Disponible en: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_8-sp.pdf

3. Dietz WH, Baur LA, Hall K, Puhl RM, Taveras EM, Uauy R, et al. Management of obesity: improvement of health-care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2521-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61748-7

4. Kovalskys I, Martinetti M, Armeno M, Tonietti M, Mazza C. Prevención de obesidad. En: Setton D, Sosa P, editors . Obesidad: guías para su abordaje clínico [Internet]. Buenos Aires: Comité Nacional de Nutrición; 2015. p. 42-7. Disponible en: https://www.sap.org.ar/uploads/consensos/obesidad-gu-iacuteas-para-su-abordaje-cl-iacutenico-2015.pdf

5. Londoño CC, Tovar MG, Barbosa DN, Sánchez C. Sobrepeso en escolares: prevalencia, factores protectores y de riesgo en Bogotá. Bogotá: Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario; 2009. 85 p. doi: https://doi.org/10.48713/10336_1356

6. Sherman J, Muehl Hoff E. Developing a nutrition and health education program for primary schools in Zambia. J Nutr Educ Behav [Internet]. 2007;39(6):335-42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2007.07.011

7. Spinelli A, Buoncristiano M, Kovacs VA, Yngve A, Spiroski I, Obreja G, et al. Prevalence of Severe Obesity among Primary School Children in 21 European Countries. Obes Facts [Internet]. 2019;12(2):244-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000500436

8. Mendoza Charris H, Martínez L, Pérez Pérez O, Contreras LM, Barbosa Sarabia V, Ricaurte Rojas C, et al. Protocolo de intervención para el control metabólico de niños con sobrepeso y obesidad. Barranquilla: Ed. Mejoras; 2017.

9. Cigarroa I, Sarqui C, Zapata-Lamana R. Efectos del sedentarismo y obesidad en el desarrollo psicomotor en niños: una revisión de la actualidad latinoamericana. Rev Univ Salud [Internet]. 2016;18(1):156-69. doi: https://doi.org/10.22267/rus.161801.27

10. Morales Arandojo MI, Pacheco Delgado V, Morales Bonilla JA. Influencia de la actividad física y los hábitos nutricionales sobre el riesgo de síndrome metabólico. Enfermería Global [Internet]. 2016;15(4):209-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.15.4.236351

11. Alba-Martin R. Prevalencia de obesidad infantil y hábitos alimentarios en educación primaria. Enferm glob [Internet]. 2016;15(2):40-62. doi: https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.15.2.212531

12. Álvarez-Dongo D, Sánchez-Abanto J, Gómez-Guizado G, Tarqui-Mamani C. Sobrepeso y obesidad: prevalencia y determinantes sociales del exceso de peso en la población peruana (2009-2010). Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica [Internet]. 2012;29(3):303-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2012.293.362

13. Oliva Chávez OH, Fragoso Diaz S. Consumo de comida rápida y obesidad, el poder de la buena alimentación en la salud. RIDE [Internet]. 2013;4(7):176-99. doi: https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v4i7.93

14. Castronuovo L, Gutkowski P, Tiscornia V, Allemandi L. Las madres y la publicidad de alimentos dirigida a niños: percepciones y experiencias. Salud Colectiva [Internet]. 2016;12(4):537-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.18294/sc.2016.928

15. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición ENSANUT [Internet]. Centro de Investigación y Evaluación de Encuestas. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. México. 2018. Disponible en: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/index.php

16. Gutiérrez RD. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición ENSANUT, 2012 [Internet]. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública México; 2012. Disponible en: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2012/index.php

17. Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF). Encuesta Nacional de Situación Nutricional ENSIN 2015. Infografía Situación Nutricional 5 a 12 años y 13 a 17 años [Internet]. Colombia; 2015. Disponible en: https://www.icbf.gov.co/bienestar/nutricion/encuesta-nacional-situacion-nutricional#ensin3

18. Gómez MM. Capítulo dos. Violencia por prejuicio. En: Motta C, Sáez M, editoras. La mirada de los jueces. Sexualidades diversas en la jurisprudencia latinoamericana. Tomo 2 [Internet]. Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre/American University Washington College of Law/Center for Reproductive Rights; 2008. p. 90-190. Disponible en: https://redalas.net/producciones/la-mirada-de-los-jueces-sexualidades-diversas-en-la-jurisprudencia-latinoamericana

19. Ozuna B, Cotti A, Krochik G, Evangelista P, Cabrera A, Buiras V. Complicaciones de la obesidad infantil. En: Setton D, Sosa P, coordinadoras. Obesidad: guías para su abordaje clínico [Internet]. Buenos Aires: Comité Nacional de Nutrición; 2015. p. 18-35. Disponible en: https://www.sap.org.ar/uploads/consensos/obesidad-gu-iacuteas-para-su-abordaje-cl-iacutenico-2015.pdf

20. Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS [Internet]. 2008 Ago;(Suppl 2):S67-79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62

21. Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2003;57(1):13-24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0

22. Dovidio JF, Major B, Crocker J. Stigma: Introduction and Overview. En: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. p. 1-28.

23. Andrade de Souza MG. Prejuicio, estereotipo y discriminación: un análisis conceptual a partir del caso de la “aporofobia”. En V Simposio de la Renta Básica; 2005 oct 20-21; Valencia, España: Red Renta Básica; 2005. p. 1-21.

24. Cárdenas M, Gómez F, Méndez L, Yáñez S. Reporte de los niveles de prejuicio sutil y manifiesto hacia los inmigrantes bolivianos y análisis de su relación con variables psicosociales. Psicoperspectivas [Internet]. 2011;10(1):125-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol10-Issue1-fulltext-134

25. Rodríguez Navarro H, Retortillo Osuna Á. El prejuicio en la escuela. Un estudio sobre el componente conductual del prejuicio étnico en alumnos de quinto de primaria. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado [Internet]. 2006;20(2):133-49. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10201/128315

26. Saad E, Belfort E, Camarena E, Chamorro R, Martínez JC, editores. Experiencias y evidencias en psiquiatría. Puerto Vallarta: Ediciones Científicas APAL; 2010. 1261 p.

27. Simbaqueba J, Pantoja C, Castiblanco B, Ávila C. Voces Positivas. Resultados del índice de estigma en personas que viven con VIH en Colombia. Bogotá: Ifarma/Recolvih; 2010. 97 p. Disponible en: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/INEC/INTOR/informe-voces-positivas.pdf

28. Emlet CA. Experiences of stigma in older adults living with HIV/AIDS: A mixed-methods analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS [Internet]. 2007;21(10):740-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2007.0010

29. Goffman E. Estigma: la identidad deteriorada. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu; 1970. 172 p.

30. Major B, Dovidio JF, Link B, Calabrese S. Stigma and Its Implications for Health: Introduction and Overview. En: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, editores. The Oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health [Internet]. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. p. 3-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190243470.013.1

31. Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol [Internet]. 2005;56:393-421. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137

32. Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, Stewart A, Phetlhu R, Dlamini PS, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs [Internet]. 2007;58(6):541-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x

33. Van Brakel WH. Measuring Health-related stigma - A literature review. Psychol Health Med [Internet]. 2006;11(3):307-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600595160

34. Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The Impact of Stigma in Healthcare on People Living with Chronic Illnesses. J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2012;17(2):157-68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311414952

35. Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH) y Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA). Compendio sobre la igualdad y no discriminación. Estándares Americanos. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.171 Doc. 31; 2019 feb 12: Cidh.org: 2019. 184 p. Disponible en: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/Compendio-IgualdadNoDiscriminacion.pdf

36. González-Gavaldón B. Los estereotipos como factor de socialización en el género. Comunicar [Internet]. 1998;6(12):78-88. doi: https://doi.org/10.3916/C12-1999-12

37. Méndez Moreno JP, Rico Bovio A. Educación, cultura, estereotipos, cuerpo, género y diferencias sociales en la fotografía de moda. IE REDIECH [Internet]. 2018;9(17):165-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.33010/ie_rie_rediech.v9i17.148

38. Hayes N. Los estereotipos culturales como obstáculo para la convivencia en la escuela inclusiva. Tejuelo [Internet]. 2013;18:101-14. Disponible en: https://tejuelo.unex.es/tejuelo/article/view/2556

39. Morrison K. Breaking the Cycle: Stigma, Discrimination, Internal Stigma, and HIV [Internet]. Washington DC: USAID/PolicyProject; 2006. 16 p. Disponible en: http://www.policyproject.com/abstract.cfm?ID=2602

40. Morales-Domínguez JF, Moya-Morales MC, Gaviria-Stewart E, coordinadores. Psicología Social. 3 ed. Madrid: McGraw-Hill; 2009. 917 p.

41. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. The 1st International Conference of Health Promotion [Internet]. 1986 nov 21; Ottawa, Canadá: World Health Organization; 1986. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference

42. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco). World Conference on Education for All [Internet]. París: La organización; 1990. 40 p. Disponible en: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000085625

43. Martínez-Royert JC, Pulido-Rojano A, Maury Mena S, Carrero González C, Orostegui Santander MA, Pájaro-Martínez MC, et al. Anthropometric parameters regarding the nutritional status of schoolchildren. Elementary Education Online [Internet]. 2021;20(4):882-91. Available from: https://ilkogretim-online.org/index.php/pub/article/view/5318

44. Centro Cochrane Iberoamericano. Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, versión 5.1.0 [Internet]. Barcelona: Centro Cochrane Iberoamericano; 2011. 639 p. Disponible en: https://es.cochrane.org/sites/es.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Manual_Cochrane_510_reduit.pdf

45. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;25(9):603-605. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

46. Olvera N, Leung P, Kellam SF, Liu J. Body fat and fitness improvements in Hispanic and African American girls. J Pediatr Psychol [Internet]. 2013 Oct;38(9):987-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst041

47. Gray WN, Kahhan NA, Janicke DM. Peer victimization and pediatric obesity: A review of the literature. Psychol Schs [Internet]. 2009;46(8):720-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20410

48. McNamara E, O´Mahoy D, Murray A. Growing Up in Ireland. National Longitudinal Study of Children. Design, instrumentation and procedures for cohort ´08 of Growing Up in Ireland at 9 years old (wave 5) [Internet]. Dublín: Minister for Children and Youth Affairs; 2020. 125 p. http://aei.pitt.edu/102742/1/BKMNEXT394.pdf

49. Kukaswadia A, Craig W, Janssen I, Pickett W. Obesity as a Determinant of Two Forms of Bullying in Ontario Youth: A Short Report. Obes Facts [Internet]. 2011;4(6):469-72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000335215

50. Damiano SR, Yager Z, McLean SA, Paxton SJ. Achieving body confidence for young children: Development and pilot study of a universal teacher-led body image and weight stigma program for early primary school children. Eat Disord [Internet]. 2018;26(6):487-504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1453630

51. Brixval CS, Rayce SLB, Rasmussen M, Holstein BE, Due P. Overweight, body image and bullying - an epidemiological study of 11- to 15-years old. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2012;22(1):126-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr010

52. Lumeng JC, Forrest P, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH. Weight status as a predictor of being bullied in third through sixth grades. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2010;125(6):e1301-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0774

53. McCormack LA, Laska MN, Gray C, Veblen-Mortenson S, Barr-Anderson D, Story M. Weight-related teasing in a racially diverse sample of sixth-grade children. J Am Diet Assoc [Internet]. 2011;111(3): 431-6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.021

54. Roddy S, Stewart I. Children’s implicit and explicit weight-related attitudes. Ir J Psychol [Internet]. 2012;33(4):166-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2012.677996

55. Olsen B, Ritchey P, Mesnard E Nabors L. Factors Influencing Children’s Attitudes Toward a Peer Who Is Overweight. Contemp Sch Psychol [Internet]. 2020;24(1):146-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00259-8

56. Walter O, Shenaar-Golan V. Effect of the Parent-Adolescent Relationship on Adolescent Boys' Body Image and Subjective Well-Being. Am J Mens Health [Internet]. 2017 Jul;11(4):920-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988317696428

57. Gmeiner MS, Warschburger P. Intrapersonal predictors of weight bias internalization among elementary school children: a prospective analysis. BMC Pediatr [Internet]. 2020;20:1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02264-w

58. Sikorski C, Luppa M, Brähler E, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Obese children, adults, and senior citizens in the eyes of the general public: results of a representative study on stigma and causation of obesity. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021;7(10):1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046924

59. Hunger JM, Tomiyama AJ. Weight labelling and obesity: a longitudinal study of girls aged 10 to 19 years. JAMA Pediatr [Internet]. 2014;168(6):579-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.122

60. Mustillo SA, Budd K, Hendrix K. Obesity, labeling, and psychological distress in late-childhood and adolescent black and white girls: the distal effects of stigma. Soc Psychol Q [Internet]. 2013;76(3):268-89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272513495883

61. Hutchinson SM, Mueller U. Explicit and Implicit Measures of Weight Stigma in Young Children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly [Internet]. 2018;64(4):427-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.64.4.0427

62. Madowitz J, Knatz S, Maginot T, Crow SJ, Boutelle KN. Teasing, depression, and unhealthy weight control behavior in obese children. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2012;7(6):446-52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00078.x

63. Rodríguez-Ojea MA, González FN, González AT. Estigmatización de la obesidad por escolares primarios de La Habana. RCAN [Internet]. 2011;21(1):71-9. Disponible en: https://revalnutricion.sld.cu/index.php/rcan/article/view/545/590

64. Amini M, Djazayery A, Majdzadeh R, Taghdis MH, Sadrzadeh-Yeganeh H, Eslami-Amirabadi M. Children with Obesity Prioritize Social Support against Stigma: A Qualitative Study for Development of an Obesity Prevention Intervention. Int J Prev Med [Internet]. 2014;5(8):960-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4258668/

65. Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the Modified Weight Bias Internalization Scale. Body Image [Internet]. 2014;11(1):89-92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.09.005

66. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res [Internet]. 2008;23(2):347-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym052

67. Kornilaki EN. Obesity bias in children: the role of actual and perceived body size. Infant Child Dev [Internet]. 2015;24(4):365-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1894

68. Gigirey Vilar A, Rodríguez Fernández JE, Ramos Vizcaíno A. Conductas psicosociales asociadas a la obesidad infantil observadas por el alumnado de educación primaria en las clases de educación física. Trances: Transmisión del conocimiento educativo y de la salud [Internet]. 2018;10(2):217-36. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6436033

69. Schvey NA, Marwitz SE, Mi SJ, Galescu OA, Broadney MM, Young-Hyman D, et al. Weight-based teasing is associated with gain in BMI and fat mass among children and adolescents at-risk for obesity: a longitudinal study. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2019;14(10):e12538. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12538

70. Reulbach U, Ladewig EL, Nixon E, O'Moore M, Williams J, O'Dowd T. Weight, body image and bullying in 9-year-old children. J Paediatr Child Health [Internet]. 2013;49(4): E288-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12159

71. Papp I, Túry F. The stigmatization of obesity among Gypsy and Hungarian children. Eat Weight Disord [Internet]. 2013;18(2):193-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-013-0033-z

72. Bird EL, Halliwell E, Diedrichs PC, Harcourt D. Happy being me in the UK: A controlled evaluation of a school-based body image intervention with pre-adolescent children. Body Image [Internet]. 2013;10(3):326-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.02.008

73. Damiano SR, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH, McLean SA, Gregg KJ. Dietary restraint of 5-year-old girls: Associations with internalization of the thin ideal and maternal, media, and peer influences. Int J Eat Disord [Internet]. 2015;48(8):1166-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22432

74. Jendrzyca A, Warschburger P. Weight stigma and eating behaviours in elementary school children: A prospective population-based study. Appetite [Internet]. 2016;102(1):51-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.005

75. Ross A, Paxton SJ, Rodgers RF. Y’s Girl: Increasing body satisfaction among primary school girls. Body Image [Internet]. 2013;10(4):614-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.009

76. Guardabassi V, Tomasetto C. Weight status or weight stigma? Obesity Stereotypes-Not excess Weight-Reduce working memory in school-aged children. J Exp Child Psychol [Internet]. 2020;189:104706. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104706

77. Chan KL, Lee CSC, Cheng CM, Hui LY, So WT, Yu TS, et al. Investigating the Relationship Between Weight-Related Self-Stigma and Mental Health for Overweight/Obese Children in Hong Kong. J Nerv Ment Dis [Internet]. 2019;207(8):637-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001021

78. Wong PC, Hsieh Y-P, Ng HH, Kong SF, Chan KL, Au TYA., et al. Investigating the self-stigma and quality of life for overweight/obese children in Hong Kong: a preliminary study. Child Ind Res [Internet]. 2019;12:1065-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9573-0

79. Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2004;113(5):1187-94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1187

80. Strauss RS. Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2000;105(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.1.e15

81. Losada AV, Rijavec MI. Consecuencias psicológicas en niños con obesidad producto de la estigmatización social. Revista Neuronum [Internet]. 2017;3(2):1-20. Disponible en: https://eduneuro.com/revista/index.php/revistaneuronum/article/view/95

82. Elizathe L, Murawski B, Rutsztein G. La cultura de la delgadez en los niños. Encrucijadas [Internet]. 2010;(50). Disponible en: https://tinyurl.com/ynf9n5ty

83. Bautista-Díaz ML, Márquez Hernández AK, Ortega-Andrade NA, García-Cruz R, Álvarez-Rayón G. Discriminación por exceso de peso corporal: Contextos y situaciones. Rev Mex de trastor aliment [Internet]. 2019;10(1):121-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.22201/fesi.20071523e.2019.1.516

84. Tiggemann, M, & Anesbury, T. Negative stereotyping of obesity in children: the role of controllability beliefs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, [Internet]. 2000;30(9), 1977-1993. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02477.x

85. Suriá-Martínez R. Estereotipos y prejuicios. En Suriá-Martínez R, organizador. Psicología Social (Sociología). Curso 2010/11 [Internet]. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante; 2010. 12 p. Disponible en: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/14289

86. Cruz Sánchez M, Tuñón Pablos E, Villaseñor Farias M, Álvarez Gordillo GC, Nigh Nielsen RB. Sobrepeso y obesidad: una propuesta de abordaje desde la sociología. Regsoc [Internet]. 2013;25(57):165-202. doi: https://doi.org/10.22198/rys.2013.57.a115

87. Zuba A, Warschburger P. The role of weight teasing and weight bias internalization in psychological functioning: a prospective study among school-aged children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2017;26(10):1245-55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-0982-2

88. Solbes I, Enesco I. Explicit and implicit anti-fat attitudes in children and their relationships with their body images. Obesity Facts [Internet]. 2010;3(1):23-32. https://doi.org/doi:10.1159/000280417

89. Dietz WH. Overweight in childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2004;350(9):855-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp048008

90. Ministerio de Educacion de Colombia (MinEducación). Lineamientos técnico-administrativos y estándares del Programa de Alimentación (PAE). Version transitoria, mayo 2013 [Internet]. Bogotá: la entidad; 2013. 135 p. Disponible en: https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-235135_archivo_pdf_lineamientos_tecnicos.pdf

Appendix

Appendix. of the included studies (n=31).

| Item | First author and year of publication | Type of study | Sample, gender, ethnicity, school grade, socioeconomic level | Average age | Country of the study | Instruments used | Synthesis of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amini et al. 2014 [64] | Qualitative study, content analysis technique | 27 children (11 boys, 16 girls); 5th grade | 10-11 years | Iran | Debates, in 4 focus groups, on weight loss barriers, weight labelling, social stigma of overweight or obesity | Nine themes emerged in three main categories. Barriers to weight loss included environmental, psychological and physiological barriers. The component category of the intervention included improved nutrition, physical activity promotion, social support and education. The environment and implementation of the intervention were included in the category of conditions of intervention. The children proposed a multi-component approach to the development of an intervention. Improved nutrition and physical activity; social support and education were mentioned as key elements of effective intervention |

| 2 | Bird et al, 2013 [72] | Randomized clinical trial ACE | 98 children (43 boys y 45 girls) | 10-11 years | Bristol, United Kingdom | Intervention with the "Happy Being Me" program with control group, body satisfaction measures, negative body image risk factors, eating behaviors, self-esteem and knowledge of the topic of intervention, at the beginning, after the procedure and at follow-up 3 months later. | At baseline there were no differences in the BMI of girls (t = 0.41, gl = 13, p = 0.69, η2 = 0.01; Intervention M = 20.17, SD = 6.31; Control M = 19.11, SD = 3.62), or in age (t = 1.24, gl = 40, p = 0.90, η2 = 0.02; Intervention M = 10.70, DE = 0.47; Control M = 10.68, DE = 0.48) between the conditions for intervention and control. Among boys, at baseline, there were no differences in BMI (t = 0.61, gl = 16, p = 0.55, η2 = 0.02; Intervention M = 16.30, SD = 1.95; Control M = 16.88, SD = 2.03), or age (t = 1.48, gl = 44, p = 0.15, η2 = 0.02; Intervention: M = 10.39, SD = 0.50. Girls' participation in the intervention resulted in significant improvements in body satisfaction, appearance-related conversations, appearance comparisons, eating behaviors and knowledge of the intervention topic, although body satisfaction was not improved or worsened. There was also a significant decrease in the internalization of ideals of cultural appearance from start to follow-up. Boys' participation in the intervention resulted in significant improvements in post-intervention internalization and appearance comparisons. However, none of these changes remained during follow-up after three months. There was no improvement in the control group over time |

| 3 | Brixval et al., 2012 [51] | Cross-sectional study | 4.781 children | 11,13 y 15 years | Denmark | Program "Behavior of School-age Children", of 2002, that measured bullying due to overweight or obesity, analysis by gender, body image | In this study, 11.2% had been exposed to bullying 2-3 times a month or more in recent months. In addition, 8.6% were classified as overweight and 1.1% as obese. Bivariate logistic regression analyses showed that, among students exposed to bullying, there was a statistically significant accumulation of overweight students (P < 0.000), students with lower grades (P < 0.000), students who do not consider their bodies to be of adequate size (P < 0.000) and students with lower family social class (P < 0.000). This tendency was also present when it was stratified by gender. In addition, there was a statistically significant accumulation of girls from non-traditional families exposed to harassment (P= 0.001). A significant association, with a U-shaped pattern, between body image and harassment exposure was shown in a logistic regression analysis (P <0.000). Students who are not satisfied with their body image, who feel too thin or fat, are more likely to be bullied. Overweight and obese students were more exposed to bullying than their normal-weight peers. Odds ratios (OR) for bullying exposure were 1.75 (1.18-2.61) in overweight boys and 1.98 (0.79-4.95) in obese boys. As for the girls, the corresponding OR were 1,89 (1,25-2,85) in those with excess weight and 2,74 (0,96-7,82) in obese girls. Body image fully mediated the associations between weight and exposure to bullying in both boys and girls |

| 4 | Chan et al., 2019 [77] | Correlational study | 367, (198 boys, 169 girls) | 8-12 years | Hong Kong | Weight Bias Internalization Scale [WBIS]; Weight Self Stigma Questionnaire [WSSQ]) and Mental Health Conditions (Short Symptom Rating Scale [BSRS-5]). | Compared to non-OW children (n = 241; 143 children), OW children (n = 114; 55 children) had higher weight-related self-stigma in the WBIS (26.49 8.68 vs. 21.58 7.54; P <.) and in WSSQ scores (26.36 8.98 vs. 21.91 8.71; P <.). No significant differences were found between OW and non-OW children in mental health conditions, as reflected in the BSRS-5 score (4.29 4.35 vs. 4.44 4.16; P =.). BSRS-5 was significantly associated with WBIS. OW children tended to have a higher level of self-stigma; those with a higher level of weight-related self-stigma had more mental health problems |

| 5 | Damiano et al., 2018 [50] | pilot study for ACE | 51 children | 5-8 years | Melbourne, Australia | Program "Achieving Body Confidence for Young Children" ABC-4-YC, interviews about body esteem and body image | We found a significant improvement in body esteem and positive feedback from teachers. The results provide preliminary support for ABC-4-YC to improve children’s body image attitudes, but a thorough evaluation is needed |

| 6 | Damiano, et al., 2015 [73] | Mixed study | 111 girls and 109 mothers of girls | 5 years | Melbourne, Australia | Interviews and questionnaires on internalization of thinness bias, dietary restrictions | 34% of girls reported at least a moderate level of dietary restriction. While most girls were satisfied with their body size, half showed some internalization of the ideal of thinness. Dietary restriction of girls was correlated with weight bias favoring thinner bodies and greater internalization of the ideal of thinness, media exposure, and talk about appearance with peers. Media exposure and talk about appearance were the strongest predictors of dietary restriction |

| 7 | McNamara, et al., 2020 [48] | Experimental study protocol, inter and intra-subjects | 176 children, 92 boys, 84 girls; 4th, 5th, 6th grade | 9-12 years | Ireland | Program "Growing Up in Ireland", questionnaires on the context of social stigma due to overweight or obesity | The data allowed to examine simultaneously multiple factors of various levels of life of the child and his or her environment (family, neighborhood, school, time period), while longitudinal design allowed trajectories that change over time to be modeled |

| 8 | Gigirey Vilar, et al., 2018 [68] | Cross-sectional study | 310 (174 boys, 136 girls); 5th and 6th grade | 9-12 years | Santiago de Compostela, Spain | Questionnaire (LópezRoldán & Fachelli, 2015; Martínez-Olmo, 2002) | The results showed that there is rejection towards overweight and obese companions, generating mockery and other negative behaviors that can lead to bullying. Regular physical exercise, a balanced diet and an education in values could contribute decisively to reduce the high rates of childhood obesity and mitigate, in a way, the problems that arise from it |

| 9 | Gmeiner y Warschburger, 2020 [57] | prospective cohort study | 1463 children (707 boys, 756 girls); different socioeconomic levels | 6-11 years | Brandenburg, Germany | Three measurements: target weight status, weight-related teasing and body dissatisfaction. | A lower educational level of parents, a greater weight of the child, the female gender, the experience of teasing, a greater body dissatisfaction, a greater relevance of the figure and higher scores of depression were predictive of higher WBI scores. Body dissatisfaction (only for girls) and the relevance of own figure (both genders) mediated the association between self-esteem and WBI; no weight-related differences were observed |

| 10 | Gray et al., 2011 [47] | cross-sectional qualitative study | 157 children | 7-17 years | Gainesville, Fl., USA | Interviews about victimization among peers due to social stigma of overweight or obesity | Future directions are provided to address peer victimization and its impact on the behavioral and social psychological functioning of overweight and obese children, limitations of existing literature and highlight potential research areas that can provide information for the development of effective interventions to tackle the victimization of obese youth |