How to build measurable operational goals? A taxonomy of outcome measures for vocal intervention monitoring

¿Cómo construir objetivos operacionales medibles? Una taxonomía de criterios de logro para el monitoreo de la intervención vocal

Abstract

Introduction: The complexity of the vocal phenomenon hinders the therapist's ability to quickly and effectively monitor the achievements obtained by the patient through vocal intervention. The assessment of therapeutic progress relies on the therapist's capability to utilize valid, reliable, and meaningful outcome criteria.

Aim: Develop a conceptual framework of outcome measures to be used in the treatment plans designed by speech therapists when attending to patients with vocal complaints.

Methodology: Qualitative, conceptual, and model-type research in which a critical review is conducted through a non-probabilistic theoretical sampling of the theoretical models of therapy treatment plans, the outcome measures involved and their relevance to voice intervention. Building upon this, a taxonomy of outcome measures is proposed for verifying therapeutic progress in voice therapy.

Results: A conceptual outcome measures framework is proposed. This model incorporates quantitative, qualitative, and mixed criteria to monitor the diverse aspects of vocal function in the context of voice intervention.

Conclusion: The model provides a precise guide to assess the results achieved by the patient in vocal intervention through treatment goals.

Keywords

Treatment planning; goals; achievement; voice; voice disorders; speech therapy; voice training; rehabilitation.

Resumen

Introducción: La complejidad del fenómeno vocal dificulta que el/la terapeuta monitoree de manera rápida y eficaz los logros obtenidos por el/la usuario/a mediante la intervención fonoaudiológica. La evaluación del avance terapéutico depende de la habilidad del/la terapeuta para emplear criterios de medición válidos, confiables y significativos.

Objetivo: Desarrollar un modelo teórico de criterios de logro para su consideración en la formulación de los objetivos operacionales en las planificaciones terapéuticas que emplean los profesionales fonoaudiólogos en la atención de usuarios/as que presentan queja vocal.

Metodología: Investigación cualitativa, de tipo conceptual y modélica, en la que se lleva a cabo una revisión crítica de la literatura a través de un muestreo teórico no probabilístico de los modelos teóricos propuestos para la formulación y medición de objetivos en el contexto terapéutico y sus alcances respecto de la intervención vocal. A partir de ello, se propone una taxonomía de criterios de logro para la verificación del avance terapéutico.

Resultados: Se propone una taxonomía organizada en torno a criterios de logro cuantitativos, cualitativos y mixtos, los que son propuestos para el monitoreo de diversos aspectos de la función vocal en el contexto de la intervención fonoaudiológica.

Conclusión: El modelo proporciona una guía precisa para evaluar de manera efectiva el progreso y los resultados alcanzados por el/la usuario/a en el abordaje fonoaudiológico vocal a través de los objetivos operacionales planteados para la intervención.

Palabras clave

Planificación terapéutica; objetivos; logro; voz; disfonía; fonoaudiología; entrenamiento vocal; rehabilitación.

Introduction

Voice intervention for patients with vocal needs requires the professional to develop an appropriate treatment planning process. This process is critical to the effectiveness of voice therapy and should consider both the goal-setting and intervention mechanisms based on the information obtained during the assessment process [1,2]. The treatment planning process affects intervention quality and patient autonomy while offering measurement tools for voice treatment progress [3].

Treatment planning goals are categorized into varying levels of abstraction based on the hierarchical structure of the theoretical framework used [4,5]. In this sense, for example, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [6] organizes goals into two levels: long-term and short-term. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [7] suggests an intermediate level in the clinical goals' hierarchy, considering temporal criteria for their organization. Dekker et al. [8] classify the goals into three levels based on their nature rather than temporal organization. Thus, the following goals are noted: fundamental goals, which reflect the patient's vision of his or her future; functional goals, which are related to the reduction of limitations in functioning; and symptom goals or pathology goals, which are directly related to the intervention of the health condition affecting the patient. Crisosto [9] also categorizes the treatment goals into three proposed categories based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health [10]. This proposal differentiates between a general goal, focused on the Participation/Activity level, and specific and treatment goals, both aimed at addressing the Structure/Function level, varying in specificity and detail. By implementing a three-level precision organization, it becomes feasible to differentiate hierarchically diverse stages to accomplish the final or general goal. Consequently, it is possible to create a scale for operationalizing activities related to implementing planned interventions and facilitating therapeutic activity [11-13].

This study seeks to develop a taxonomy of outcome criteria for organizing the measurement of specific goals in vocal intervention. Due to space constraints, this taxonomical classification focuses on measuring goals or targets [14] related to vocal quality using a direct method [15] while excluding vocal hygiene and counseling interventions. The therapeutic intervention of other aspects, along with the impact of vocal changes on a patient's quality of life, known as aims in the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System (RTSS) model [14,16], and how these are linked to changes in their daily activities, requires a different conceptual framework beyond the scope of this proposal but still important to acknowledge.

Theoretical models for goal setting and measurement in therapy and their scope for vocal intervention

Currently, there are many theoretical approaches with different levels of impact. These approaches aim to provide tools to organize an adequate intervention plan, although, to date, none is considered the gold standard procedure [14]. Moreover, most of these frameworks have not been specifically designed or modified for speech-language, let alone vocal, purposes. Many are derived from different fields or focus on health resource management or interdisciplinary work, making their application less specific. Consequently, specific incompatibilities become evident when comparing these models to the conditions of vocal intervention.

Goal setting in rehabilitation may not always align with the proposed therapeutic ideologies or theoretical frameworks. There has been discussion about whether these ideologies are used in therapy for certain patients [17,18], but more attention has been given to this issue in recent years to organize interventions better [19-21]. Research in this particular vocal area is limited, except for a few exceptions that vary in their methods, goals, and scope [9,14,15,22-25] but do not specify methods or criteria for monitoring therapeutic progress in a specific manner.

When examining the different approaches to goal setting, it is clear that there are similarities and differences in the recommendations made by authors and the factors to be considered. There are at least twelve recognized philosophies of goal setting in literature, each with distinct variations [26]. Even when utilizing the same theoretical framework, there can be differing viewpoints on implementing or interpreting it, as evidenced by the SMART philosophy [27-37], indicating the considerable theoretical divergence in this issue. The wide range of models, approaches, frameworks, and tools for goal setting in rehabilitation sciences leads to significant variation in therapeutic planning and progress measurement across therapists and clinical centers [38]. Despite their diversity, there are similarities among the different understandings of goals, such as measurability and involving the patient in the goal-setting process [26].

According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) proposal [10], therapeutic intervention goals can be quantitatively measured if a given behavior or aspect of it can be defined in finite terms or qualitatively measured using a judgment scale [12,34]. This represents a challenge from a voice perspective due to the multidimensionality of the phenomenon [39,40].

Monitoring a patient's progress in rehabilitation poses a major challenge due to the therapist's ability to use valid, reliable, and meaningful measurement criteria for the goals addressed [41]. In a hypothetical scenario, patients' improvement might be attributed to measurement errors rather than therapeutic effects, considering factors such as poor inter-observer validity, easy therapeutic progression for the patient, unequal task scaling, or inappropriate outcome criteria [42,43].

Thus, strategies for measuring treatment goals are critical for a patient’s progression. In SMART [5,37] and SMARTER [29,44] methodologies, measurability is essential to setting valuable and significant goals. The proposed Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) [45] has been widely accepted as a dependable tool for assessing therapeutic success, supported by extensive evidence in the literature [34,46-48]. Thus, it offers a five-level monitoring approach but lacks specific criteria for goal assessment, which should be tailored to the patient's diagnosis and contextual factors related to their health condition. Additionally, there are no references to its application in voice therapy. Similarly, according to the SMART Goal Evaluation Method (SMART-GEM) [49,50], the measurability criterion can only be satisfied if the proposed goal includes a measurement method and an evaluation criterion for assessing the performance of the trained action.

In theoretical metrology, four scales exist to measure any observed phenomenon, which vary based on the nature of the thing being measured. Thus, the nominal scale classifies the results qualitatively in a non-hierarchical dichotomous or polychotomous organization, so it can only reflect difference, not order. The ordinal scale ranks measurements qualitatively, assuming an order based on the measured characteristic. In this scale type, the data are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, meaning they belong to only one category. Interval scales are more precise because consecutive labels or numbers establish equal intervals in addition to the order or hierarchy between categories. Even though the zero point and the measurement unit are arbitrary, the ratio between two intervals is independent of that unit and that point and is always constant. The ratio scale retains all the attributes of an interval scale but has at its origin a true zero, which is not the case for the interval scale [51-54]. In this sense, progress in therapy can be evidenced through ordinal, interval, or ratio scales because these effectively reflect a measurement hierarchy, and their choice will depend on the nature of the observed phenomenon. The nominal scale, sensitive to difference but not order, prevents adequate patient progress monitoring. In other words, a therapist or anyone assessing modifications may identify changes in specific symptoms, but determining if it indicates progress or regression requires knowledge of the patient's condition and voice physiology. This information is crucial for monitoring a patient's therapeutic progress and assessing the effectiveness of the intervention used [55,56].

Voice is the result of a multidimensional process [39]. Vocal function cannot be rated on an isolated scale alone, meaning no single measure can account for all voice characteristics simultaneously. All tests and assessment methods allow only a part of the vocal function to be studied. It is necessary to know fully which aspects of the voice are assessed or measured by the selected instruments and strategies and which are not [40].

In biological terms, the voice is produced by coordinating several multisystemic anatomical and physiological conditions. Several factors, such as motor planning, laryngeal innervation, tissue properties, vocal fold biomechanics, aerodynamics, acoustics, endocrine influence, auditory processing, and supraglottic resonant mechanisms, impact sound production and perception [57,58]. In turn, external genetic, chemical, thermal, and mechanical factors influence the biophysiological conditions and anatomical dimensions of the organs involved [59,60]. Variations in vocal dynamics will be monitored during speech therapy, as the physiological changes and anatomical modifications involved in the voice intervention will cause a variation in vocal function that will be reflected in the quality of the sound heard by the therapist.

From a socio-cultural standpoint, the patient's voice reflects their position within the contextual conditions they co-create with society [59,60]. In this sense, the voice conveys information about the patient's identity [61,62]. The speaker/voice is tied to socio-cultural categories perceived by the listener, which are not fixed characteristics but are determined by dynamic communication practices involving both the speaker and the listener [63-65]. Identities can be indexed linguistically and vocally through labels, implicatures, postures, styles, structures, or linguistic systems [66]. In this process, subjects have control over the indexical effects of their discourse and can make personal decisions about when to use specific communicative patterns [67]. A voice impairment obviously affects the latter, reducing vocal plasticity. By intervening in the vocal production parameters, patients attending vocal therapy can enhance their agency over their voice, the impact of which will be measured through outcome criteria assessed by the same patient [68]. In the trans population, for example, it is essential to consider the social and cultural processes that determine the patient's desire for vocal change [69,70].

The listening process is also relevant and completes the communicative process between the speaker-listener dyad. Hearing the voice is a crucial process that is influenced by both biophysiological variables and socio-cultural factors [60]. From the point of view of vocal assessment, perceptual evaluation of the patient's voice is recommended [39]. However, the professional judgment of therapists is always influenced by the collective vocal self-perception, which impacts the therapist and the patient [71].

To date, the complex multifactorial structure of voice has hindered the development of a taxonomy of outcome criteria for monitoring progress in therapy. Although the available voice assessment mechanisms provide a relatively comprehensive assessment of vocal function in clinical practice, these mechanisms have not been successfully integrated as progress monitoring tools in treatment goals for patients, resulting in goals being set without a means of monitoring them [22]. Without measures to assess performance, it becomes difficult to adequately plan the progress of therapeutic tasks for the patient, thus impeding the discharge process in the medium term [72].

This research proposes a taxonomic framework for monitoring treatment goals through outcome criteria so that therapists can access appropriate conceptual tools to support clinical practice.

Method

The research presents a qualitative design regarding information production techniques and data analysis strategy. The study belongs to the category of critical review according to Grant and Booth's criteria [73], which is framed in a model-type conceptual research approach [74, 75]. The study identifies essential conceptual frameworks for goal organization and measurement in voice intervention therapy planning. These theoretical schemes are evaluated based on their contribution and adequacy to the specific therapeutic task in the area, using a non-probabilistic theoretical sampling [76,77]. This sampling method involves identifying evidence or conceptual support for a specific theoretical device, in this instance, the presented model, to examine and develop the construct. The purposive sample intends to provide evidence of the theoretical manifestations contributing to the model's formation [77,78].

Purposive sampling offers an alternative to exhaustive trawling of specialized literature. Instead, specific theoretical aspects are chosen to exemplify or aid in understanding and structuring the proposed principles and ideas [60,76]. This decision is based on the complex and little-addressed nature of the object of study.

The proposal outlines a narrative structure to organize the analyzed themes and generate innovative theoretical knowledge from the critical analysis of the literature [73]. The formulated framework should not be seen as a finished product but rather as a starting point that needs empirical testing to assess its effectiveness and suitability.

This research proposes a taxonomy of outcome criteria to be considered when setting treatment goals in the therapeutic planning used by speech-language pathologists for patients with vocal complaints.

Results

Taxonomy of outcome criteria for monitoring treatment goals in vocal intervention

Clinicians often set voice treatment goals without a clear structure, making it difficult to monitor them effectively [22]. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the vocal phenomenon's multidimensionality prevents satisfactory measurement using only instrumental methods. The patient's sociocultural positioning processes [60] and emotional experience [79,80] contribute to this, along with the unpredictability and nonlinearity of the vibratory mechanism [81,82], the interaction between vocal tract configuration and vocal fold vibration characteristics [83], and other complicating parameters. In addition, voice intervention sessions require outcome criteria that can be promptly applied to guide therapeutic decisions based on the patient's immediate response to the planned intervention.

According to this proposed taxonomy, monitoring therapeutic progression involves the use of multiple outcome criteria to demonstrate the following: (1) the different improvements in vocal function during voice intervention, whose nature is variable and diverse [84]; (2) the involvement of the patient and other actors, different from the therapist, in determining goal achievement, by adopting a patient-centered approach that takes into account their environment [19,85,86] and (3) the various channels through which vocal quality information can manifest and be intervened [15].

This research puts forth a taxonomic framework grounded in theory but also provides practical tools tailored to the conditions and resources commonly encountered in vocal therapy. The proposal is solely concerned with measuring the goal. In this sense, this study does not address other aspects crucial for effective vocal therapy [87], such as the most suitable techniques or methods for patient intervention, the importance of focusing on specific vocal parameters, or the connection between the technique and treatment goals.

The outcome criteria determine how patients' vocal progress will be monitored. In simpler terms, they help determine the most effective way to measure the vocal phenomenon, or a particular aspect of it, using various strategies. Each outcome criterion is assessed by considering (1) the patient's performance-task complexity relationship [88,89], (2) the therapeutic progression stage [90], and the application of motor learning principles [91], which is the standard for assessing the outcome [49,50].

The outcome criteria presented help monitor the goals set with the highest level of specificity: treatment goals, immediate goals, short-term goals, etc. Specific and general goals, which are intangible and abstract, do not necessitate specific outcome criteria, as they aim to direct therapeutic efforts toward convergence [30]. The proposal is designed to be implemented during therapeutic sessions when treatment goals are commonly set. However, there are situations where the structure of outcome criteria could be applicable and appropriate for therapeutic activities that the patient needs to carry out independently but within the framework of vocal training or intervention.

It is important to mention that the outcome criteria mentioned here align with a theoretical organizational logic. However, it is possible to use multiple outcome criteria to monitor the same goal, enhancing the information on the patient's performance.

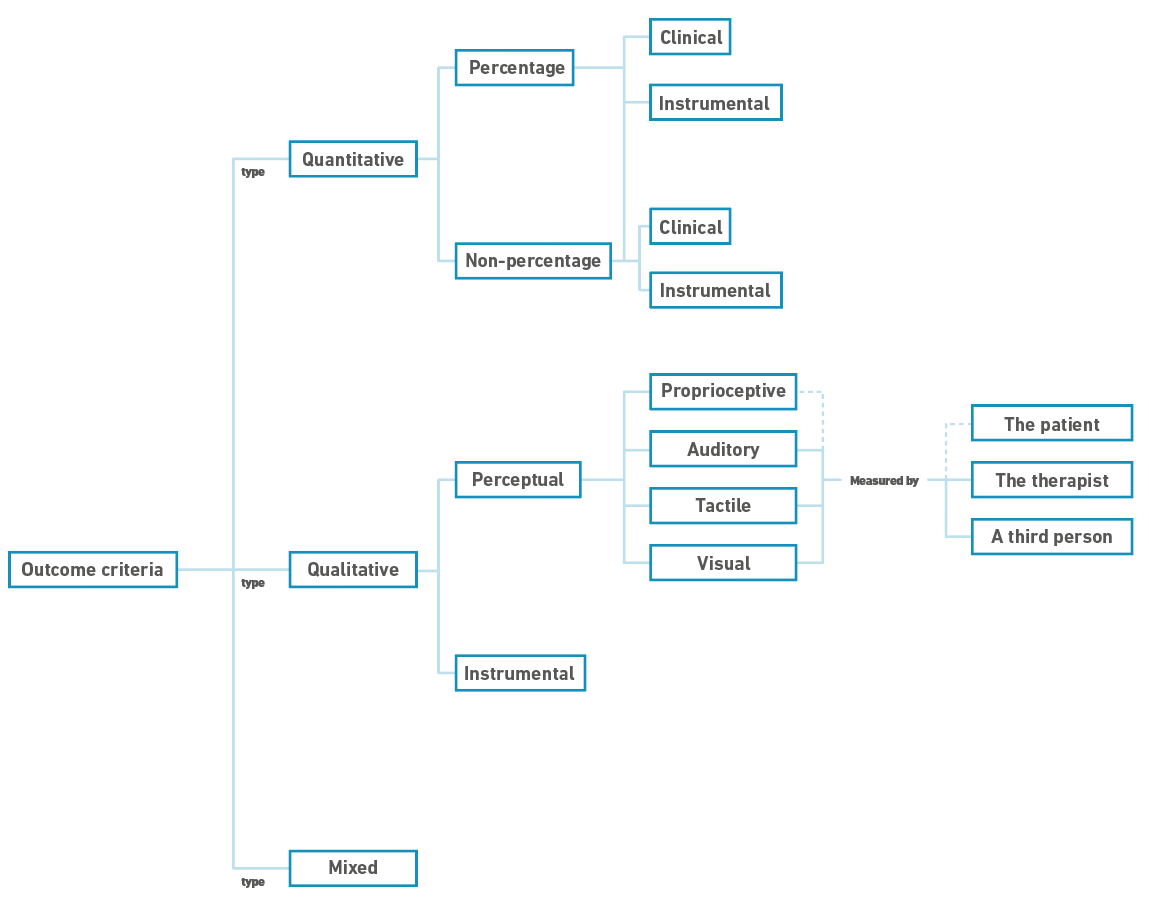

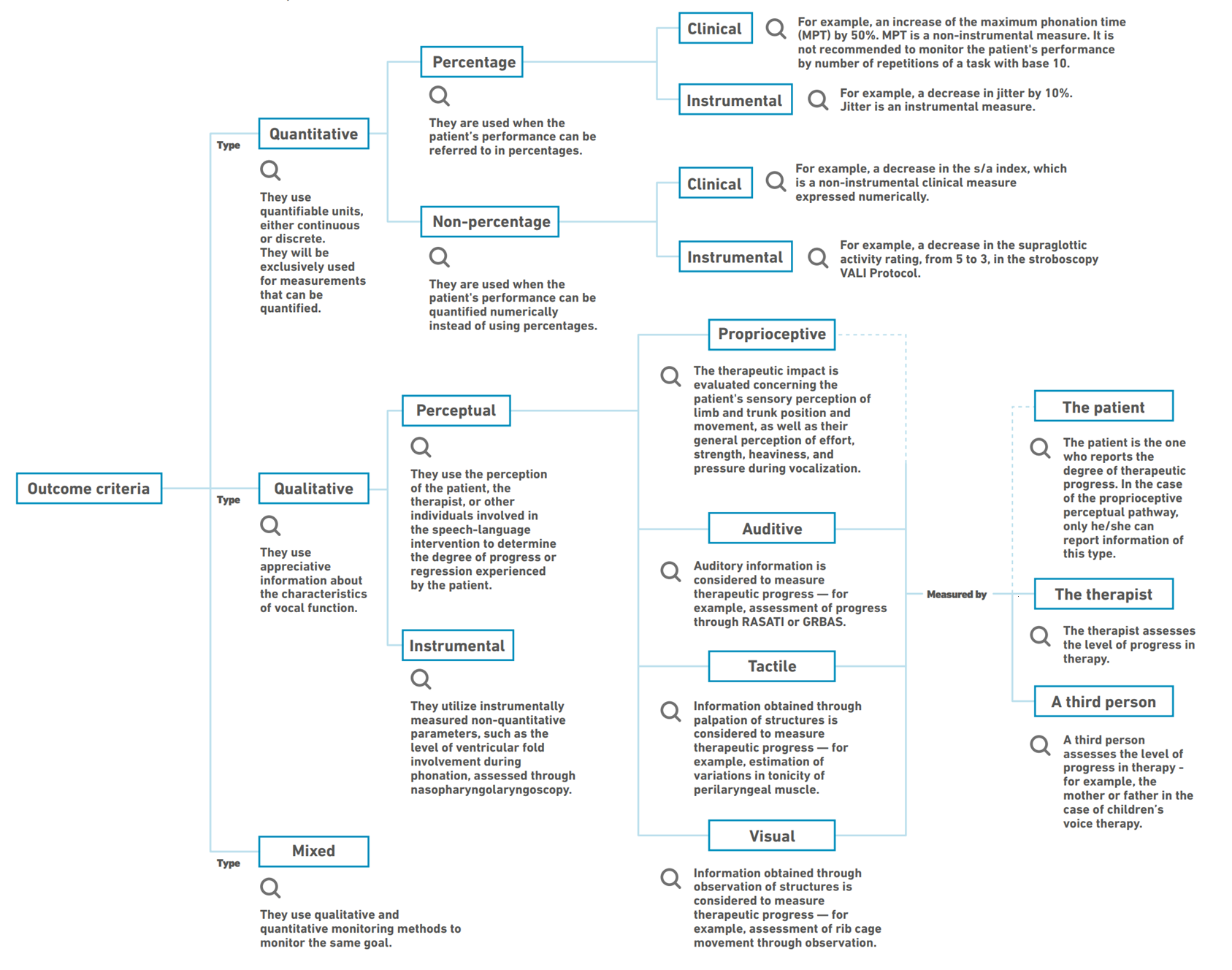

Figure 1 schematizes the proposed taxonomy of outcome criteria. It is then defined, described, and exemplified in depth. An extended version of the taxonomic model can be found in Appendix 1.

Figure 1. Diagram of the taxonomy of outcome criteria for monitoring treatment goals in vocal intervention

1. Quantitative outcome criteria

These outcome criteria use quantifiable units, either continuous or discrete, depending on the nature of what is being measured. The patient's performance outcome is quantified and compared to the initial assessment or therapeutic progression, serving as a baseline or reference for typical performance in the general population [92]. They are used exclusively for quantifiable measurements. The distinction between percentage and non-percentage quantitative criteria is not absolute, as the same quantitative outcome criterion can be measured using both methods. This classification separates them due to the impossibility of achieving commutability for specific measures and the historical use of percentage quantitative outcome criteria in the speech-language intervention [93,94].

1.1. Percentage quantitative outcome criteria

Interval or ratio outcome criteria [51-54]. This particular outcome criterion applies when patient performance can be measured on a scale with 100% representing the absolute or arbitrary maximum performance and 0% representing the true or arbitrary minimum, depending on the measurement. When using Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) [95] in therapy for children with developmental disorders, it is typical to employ 80% outcome criteria [96,97]. The same is true in the tradition of speech sound disorder intervention [94]. However, the debate continues on the ideal percentage for therapists to accurately determine behavior acquisition and generalization [98,99]. In addition, the literature emphasizes the importance of observing a certain level of performance in multiple sessions for therapeutic success [100,101]. Research is needed to address what happens in the context of vocal intervention. Other factors, including patient characteristics, session format, task distribution, and stimulus type, should be considered when choosing a percentage outcome criterion [91,102].

It is important to avoid mistakes when wording goals that assume, for example, "(...) to decrease harshness by 80% (...)", "(...) to reduce the vocal onset by 90% (...)", "(...) to increase vocal resistance by 95% (...)", as these parameters may not be quantifiable without instrumental operationalization, which could be questionable due to the nonlinear nature of the vocal mechanism [82]. Thus, if the goal is stated incorrectly, it is impossible to determine if it was achieved adequately.

This proposal defines instrumental measurements as those obtained through techniques such as laryngoscopy, electroglottography, acoustic analysis, aerodynamic assessment, electromyography, and imaging [57,103,104]. Although affordable, other "instruments" used to monitor some aspect of vocal quality, such as stopwatches or tuners, are not considered in the "instrumental" category, as they are not mentioned in the literature.

1.1.1. Clinical percentage qualitative outcome criteria

This category includes those outcome criteria that allow monitoring vocal quality through quantifiable clinical assessment strategies whose units are expressed as percentages.

One example is intervening vocally and monitoring changes in the maximum phonation time to see if the patient can increase it by 50%. In this case, the outcome criterion is a time measurement counted in seconds expressed as a percentage, given its relation to the patient’s initial performance.

The number of times a particular task is repeated can also be indicated as a percentage. In this scenario, 100% denotes the ideal number of task repetitions, while 0% indicates a basic or nonexistent performance level. The performance of an activity/exercise/technique does not directly reflect progress towards a vocal goal, as the performance of the activity/exercise/technique alone rarely represents the treatment goal. For this reason, it is not recommended to rely solely on the number of exercise repetitions to monitor therapeutic progress. However, this information may help determine which variations to include in an specific exercise.

1.1.2. Instrumental percentage qualitative outcome criteria

This category includes those outcome criteria that allow monitoring vocal quality through quantifiable instrumental assessment strategies with units expressed as percentages. The outcome criterion's percentage nature is unrelated to the numerical nature of the measurement. In other words, the percentage value does not determine whether the measurement is percentage-based. For example, such an outcome criterion can monitor vocal improvement by considering a 20% (or 10%, 30%, 40%, etc.) decrease in local jitter before the patient's intervention, a parameter measured as a percentage. In such a case, calculating the percentage of the percentage involves a recursive mathematical operation. Similarly, for example, a 10% (or 5%, 20%, 30%, etc.) increase in the pre-intervention fundamental frequency, a continuous measure, can be monitored by calculating the percentage of a numerical value.

Determining the percentage of change sought from vocal intervention will naturally vary according to the patient's vocal condition characteristics.

Given the level of preparation required by the therapist, the patient, and the environmental conditions to obtain instrumental measures [57,104], the usability of these criteria is somewhat limited. This is considering that in most cases, it is impossible to monitor the online impact of an activity/exercise/technique in real-time through these test media due to economic, time, technical, operational, and other conditions.

1.2. Non-percentage quantitative outcome criteria

Interval or ratio outcome criterion [51-54]. This outcome criterion will be used when the patient's performance can be referred to quantitatively. Calculating eventual percentages to express what is observed is optional and depends on each therapist's particular practices. That is to say, the outcome criterion can be expressed through whole numbers representing quantities or percentages to express the same information. In other words, in the case of a therapeutic intervention for a patient with 50 dB of conversational intensity to increase that volume, a goal will be set with a non-percentage outcome criterion of 5 dB increase or a percentage outcome criterion where a 10% increase is monitored.

Percentage and non-percentage quantitative outcome criteria are included in this taxonomy precisely because their similarity makes them theoretically commutable. In practice, however, one or the other is chosen, depending on the nature and numerical complexity of what is monitored.

Contrary to the percentage outcome criteria, in which the scale from 0 to 100% is defined in advance and, therefore, the maximum or expected performance is known beforehand, the mathematical identity of the non-percentage outcome criteria does not require per se a staging. For instance, it is therapeutically feasible to observe that, while reading a list of vowel-starting words, a patient can produce 3 of them without a glottal onset. In this case, the number of these three emissions is not specified concerning the total expected vocal productions, and, therefore, it is not useful from a therapeutic point of view and does not provide information for comparison with previous or subsequent performances. Therefore, it is necessary always to use a numerical reference that allows the therapist to compare the patient's performance concerning an ideal or a previous performance.

1.2.1. Clinical non-percentage quantitative outcome criteria

This category includes those outcome criteria that allow monitoring vocal quality through quantifiable clinical assessment strategies whose units are expressed numerically.

For example, a non-percentage clinical monitoring mechanism could be given by calculating the s/a (or s/e, or s/z) index to indicate glottic insufficiency [105]. In this case, it is possible to monitor the effectiveness of a series of exercises that decrease the blowing quality of the voice through exercises that increase vocal fold coaptation. Thus, the index is brought down from 1.8 to 1.3 (or 1.4, 1.5, or 1.6, etc.), which represents, in this case, an effective decrease of 0.5 points on the scale. This decrease represents a 27.77% decrease from the initial s/a index, but, in this example, it is faster and more convenient to monitor the non-percentage decrease than the percentage decrease. As noted, despite their commutability, one will probably always be used over the other, depending on what is being measured.

1.2.2. Instrumental non-percentage quantitative outcome criteria

This category includes those outcome criteria that allow monitoring vocal quality through quantifiable instrumental assessment strategies whose units are expressed numerically.

For example, the Voice-Vibratory Assessment with Laryngeal Imaging (VALI) [106], grades both anterior-posterior and medial supraglottic compression on a scale ranging from 0 to 5. The higher the number, the greater the degree of approximation of the structures. In this sense, the decrease in such activity could be monitored on a non-percentage numerical scale assessed exclusively through a laryngeal imaging test.

It is important to highlight that if the outcome criteria set out in the intervention are particular aspects of glottal function, measuring them through clinical or instrumental criteria that monitor the voice (instead of laryngeal function) may not be plausible due to the nonlinearity and dynamic-chaotic functional architecture of the vocal phenomenon [81,82]. In simpler terms, if the treatment goal is to enhance vocal fold contact, it becomes essential to perform laryngeal visualization exams to assess it. If these exams cannot be conducted during the therapy session, which is typically the case, monitoring this goal and assessing the intervention's effectiveness becomes impossible. However, if measurable clinical aspects are used to operationalize the pathophysiological condition, the outcome criterion should address this variation rather than the variation in glottic function.

2. Qualitative outcome criteria

These criteria employ appreciative-type information regarding the characteristics of vocal function, as used in the perceptual assessment of voice suggested by the European Laryngological Society, ELS [39], or ASHA [57].

Qualitative outcome criteria are ordinal and sometimes nominal [51-54], which does not depend on the taxonomic level but rather on the nature of what is being measured. A patient with vocal hyperfunction [107] might perceive a vibrating vocal sensation in the nasal-cranial region [108] during the intervention. If the patient reported proprioceptive sensations during vocal production in the laryngeal region at the start of treatment, an order in the perceptual process could be determined. From an ordinal point of view, voice perception is typically better in the nasal-cranial rather than the laryngeal region. However, if the patient experiences a vibrating sensation in the nasal bridge area and later in a higher anatomical sector, the glabella, it is impossible to rank these two areas in terms of vocal sensory suitability. The difference in this case is merely nominal because there is not enough evidence to conclude that one area is better.

According to the ICF model [10], including qualitative outcome criteria to better understand the patient’s progress throughout the intervention is a tool that should be incorporated into therapeutic interventions. This type of outcome criteria is useful, given the vocal phenomenon’s complexity, especially when considering that its nature often shuns quantification and that even instrumental examinations require the interpretative work of the clinician [40].

2.1. Perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

This type of criteria uses the perception of the patient, the therapist, or other individuals participating in the speech-language intervention to determine the degree of progress or regression experienced by the patient during the intervention. The decision on who participates in this assessment process depends on the agreements between the patient and therapist and the nature of what is being measured, and it should be explicitly mentioned in the goal [12].

As perceptual processes are highly variable and subjective [109], the observations derived from them should be interpreted cautiously during the intervention. Nevertheless, they represent a fundamental tool for (self-)evaluation (self-)correction, and (self-)cuing in the therapeutic process [15].

When there are multiple perceptual pathways for goal monitoring, it is advised to include all of them in the therapeutic planning discussion and evaluate if more than one is used to assess the patient's performance.

2.1.1. Proprioceptive perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

This category includes those outcome criteria in which proprioception information is considered. This information is related to the perception of limb and trunk position and movement, as well as the overall sense of effort, force, heaviness, and pressure, which collectively contribute to the awareness of the body's mechanical and spatial state [110,111]. Body and voice proprioception are both evaluated and monitored in the speech-language intervention [112-114], and they require the patient's exclusive assessment as they involve bodily sensations generated internally. The patient becomes aware of this activity in the intervention to monitor it in the therapeutic process. Figure 1 shows the patient's exclusive role in assessment, as indicated by the dotted line connecting the 'proprioceptive perceptual outcome criterion' and 'patient' boxes.

2.1.2. Auditory perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

This category includes the outcome criteria that consider auditory perceptual information from the patient, the therapist, or a third person regarding the voice quality of the person receiving the speech-language intervention. Deciding who will conduct voice quality verification is complex because it involves taking into account the hearing ability of patients, which is often affected by vocal alterations and can even be a causative factor of the alteration [115].

In the same way that a perceptual assessment of the voice is essential for a complete diagnostic process [39,57,116], auditory information is indispensable for an adequate (re)orientation of the therapeutic process. The monitoring process is continuous during the intervention, enabling real-time monitoring of vocal changes caused by therapeutic techniques [117]. It is widely recognized that instrumental measurements of vocal phenomena can supplement perceptual information. However, these do not have the same ecological capacity [118] as online auditory perceptual monitoring, that is, at the very moment when the voice is being produced.

2.1.3. Tactile perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

This category includes the outcome criteria that involve tactile perceptual information and could, at least in theory, be assessed by the patient or a third person, although the therapist typically does it due to their professional expertise.

This type of information is relevant to establish aspects that are not easily quantifiable in clinical practice, such as hypertonicity of the perilaryngeal or cervical muscles, often seen in vocal conditions caused by hyperfunction [107,119-122]. Additional aspects, such as the larynx position [123], its resistance to lateral movement [124], and rib cage motion during respiration-phonation [125,126], should be monitored using this method as well.

2.1.4. Visual perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

Outcome criteria in this category involve visual perceptual information that the patient, therapist, or a third party can verify. During phonation, several aspects can be visually verified by examining visual information [15], such as jaw movements during emission [127], patient posture during the intervention [128,129], thoracic movements during respiration, and tension in the extrinsic muscles of the larynx [116].

2.2. Instrumental perceptual qualitative outcome criteria

This criteria type relies on instrumentally measured non-quantitative parameters, such as biofeedback through respiratory plethysmography [130] or nasofibroscopy [131]. This type of criteria is also used in the instrumental assessments performed throughout the therapeutic intervention where the parameters measured are qualitative, such as the presence of harmonics in the spectrogram, the level of ventricular folds' approach during phonation at laryngoscopy, or the redness of the vocal fold at nasopharyngolaryngoscopy.

3. Mixed outcome criteria

This criteria type uses qualitative and quantitative methods to monitor the same goal, combining the characteristics of both methods.

Discussion

This study aimed to create and develop a taxonomy of outcome criteria for organizing treatment goal assessment in speech-language intervention. This is a step towards professionalizing the therapeutic task and aiding evidence-based therapeutic planning, making it an essential tool for monitoring patients with vocal complaints.

The lack of a specific taxonomy for treatment goals in speech-language therapy hinders progress and complicates decision-making, ultimately affecting the discharge process. This situation could result in decreased adherence to speech therapy if patients perceive the assigned tasks as either too easy or too challenging for their vocal abilities. The structure presented in this research may lead to professionals proposing interventions better suited to patients' actual performance, resulting in a more impactful speech-language intervention. It is important to differentiate this from treatments where vocal quality is not the primary focus, and the speech-language pathologist prioritizes the patient's psychosocial adjustment [132].

The taxonomic model proposed here is notable for its easy clinical application, without the need for extra funds or additional steps in therapeutic planning. Despite this, one of the main challenges to its implementation is the fast pace of patient care in certain work environments, which makes it nearly impossible to develop a thorough and rigorous treatment plan.

A typical error seen in therapists during early training is placing too much emphasis on a patient's ability to perform activities while disregarding the expected vocal effects from such activities. Often, they evaluate the ability to execute the intended task, like tongue vibration, instead of the vocal impact it should have, such as reducing vocal tension. This leads them to falsely believe they have achieved goals that are actually far from being reached. This phenomenon is likely because performance in the activity is a concrete and measurable goal, while the effect on the voice is a more complex cognitive skill. This mistake seriously undermines the effectiveness of vocal intervention. By providing a set of outcome criteria, the taxonomic proposal resulting from this research emphasizes the vocal consequence of therapeutic activities, not just the tasks, as the focus of evaluation.

The proposal suggests a primary differentiation between quantitative and qualitative criteria, although additional contrasts may aid in establishing consistent differences in future taxonomic models. This is especially relevant given the rapid technological progress we are witnessing as a society, which will likely affect our understanding of vocal intervention through new resources that do not currently exist.

It is important to remember that this taxonomy should be seen as a constantly evolving product, open to potential modifications. The intention is to promote discussion and debate among professionals in the area, not to impose a rigid framework for all treatment goals.

Future studies should examine the distinct effects of different planning methods on therapists and patients to determine if using (or not) an outcome criteria framework enhances intervention and accelerates (or not) goal achievement. Furthermore, additional models should be incorporated into this framework to include interventions based on an indirect method [15], effectively assessing vocal hygiene or counseling tasks commonly employed in speech-language interventions.

Conclusions

This review suggests a detailed taxonomy of outcome criteria for monitoring treatment goals, providing an accurate guide to effectively assess the progress and outcomes achieved by the patient in speech-language intervention through the treatment goals set for the intervention. The highlighted aspect is its usefulness in measuring treatment aims and adapting treatment plans to fit patient performance. This taxonomic model provides a solid but adaptable structure for guiding clinical practice, enhancing the professionalization of voice speech-language intervention, and emphasizing the critical role of therapeutic planning in successful intervention and discharge. However, it is crucial to recognize the need for future research to validate and extend the present proposal and its applicability in different clinical contexts. This study advances knowledge in voice speech-language pathology and offers a new structure for implementing precise and effective intervention strategies.

References

1. Reghunathan S, Bryson PC. Components of Voice Evaluation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2019 Aug;52(4):589-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2019.03.002

2. Romero L, Nercelles L, Olea K, Pérez R, Guzman M. Manual para la administración del protocolo de evaluación de la voz hablada (PEVOH). Santiago. Escuela de Fonoaudiología, Universidad de Chile; 2011. 43p.

3. Levack WM, Taylor K, Siegert RJ, Dean SG, McPherson KM, Weatherall M. Is goal planning in rehabilitation effective? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2006Sep;20(9):739-55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215506070791

4. Sivaraman Nair KP. Life goals: the concept and its relevance to rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2003 Mar;17(2):192-202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215503cr599oa

5. Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009 Apr;23(4):291-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509103551

6. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Person-centered focus on function: Voice . The Association; [citado 2023 May 31]. Available from: https://www.asha.org/siteassets/uploadedFiles/ICF-Voice-Disorders.pdf

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation Guide. Writing SMART Objectives . The Centers; [citado 2023 May 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/docs/smart_objectives.pdf

8. Dekker J, de Groot V, Ter Steeg AM, Vloothuis J, Holla J, Collette E, et al. Setting meaningful goals in rehabilitation: rationale and practical tool. Clin Rehabil. 2020 Jan;34(1):3-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215519876299

9. Crisosto J. Propuesta teórica de planificación terapéutica en el área de voz: aplicación del modelo de la CIF. Revista Chilena de Fonoaudiología. 2021 Jun;20:1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-4692.2021.58315

10. World Health Organization. Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento, de la Discapacidad y de la Salud. The Organization; 2001Sept: 282 p.

11. Ogbeiwi O. Why written objectives need to be really SMART. British Journal of HealthCare Management, 2017;23(7):324-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2017.23.7.324

12. Ogbeiwi O. General concepts of goals and goal-setting in healthcare: A narrative review. Journal of Management & Organization, 2018;27(2):324-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.11

13. Mullins LJ. Management and Organisational Behaviour. Prentice Hall; 2009.

14. Hart T, Whyte J, Dijkers M, Packel A, Turkstra L, Zanca J, et al. Manual of Rehabilitation Treatment Specification. 2018. 65 p. Disponible en: http://mrri.org/innovations/manual-for-rehabilitation-treatment-specification/

15. Van Stan JH, Roy N, Awan S, Stemple J, Hillman RE. A taxonomy of voice therapy. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015 May;24(2):101-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0030

16. Van Stan JH, Whyte J, Duffy JR, Barkmeier-Kraemer J, Doyle P, Gherson S, et al. Voice Therapy According to the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System: Expert Consensus Ingredients and Targets. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2021 Sep 23;30(5):2169-201. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00076

17. Levack WMM., Siegert RJ. Challenges in Theory, Practice and Evidence. In Siegert, RJ., Levack, WMM, editors. Rehabilitation Goal Setting. Theory, Practice and Evidence. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015. p. 3-20.

18. Levack WM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, McPherson KM. Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: how clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Nov;85(2):206-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.011

19. Scobbie L, Wyke S, Dixon D. Identifying and applying psychological theory to setting and achieving rehabilitation goals. Clin Rehabil. 2009 Apr;23(4):321-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509102981

20. Siegert RJ, McPherson KM, Taylor WJ. Toward a cognitive-affective model of goal-setting in rehabilitation: is self-regulation theory a key step? Disabil Rehabil. 2004 Oct 21;26(20):1175-83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001724834

21. Siegert RJ, Taylor WJ. Theoretical aspects of goal-setting and motivation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2004 Jan 7;26(1):1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001644932

22. Crisosto J, Flores A. Estructura de los objetivos terapéuticos en la intervención fonoaudiológica de usuarios con necesidades vocales: una revisión sistemática exploratoria. Revista Chilena de Fonoaudiología. 2022;21:1-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-4692.2022.64698

23. Castillo-Allendes A, Fouillioux C. Objetivos de intervención en voz: Una propuesta para su análisis y redacción. Revista de Investigación e Innovación en Ciencias de la Salud. 2021;3(1):125-39. doi: https://doi.org/10.46634/riics.56

24. Van Stan JH, Whyte J, Duffy JR, Barkmeier-Kraemer JM, Doyle PB, Gherson S, et al. Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System: Methodology to Identify and Describe Unique Targets and Ingredients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021 Mar;102(3):521-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.09.383

25. Ma EP, Yiu EM, Abbott KV. Application of the ICF in voice disorders. Semin Speech Lang. 2007 Nov;28(4):343-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-986531

26. Levack WM, Weatherall M, Hay-Smith EJ, Dean SG, McPherson K, Siegert RJ. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 20;2015(7):CD009727. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009727.pub2

27. Bexelius A, Carlberg EB, Löwing K. Quality of goal setting in pediatric rehabilitation-A SMART approach. Child Care Health Dev. 2018 Nov;44(6):850-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12609

28. Page J, Roos K, Bänziger A, Margot-Cattin I, Agustoni S, Rossini E, et al. Formulating goals in occupational therapy: State of the art in Switzerland. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22(6):403-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1049548

29. Hersh D, Worrall L, Howe T, Sherratt S, Davidson B. SMARTER goal setting in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology. 2012;26:220-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.640392

30. MacLeod L. Making SMART goals smarter. Physician Exec. 2012;38(2):68-70.

31. Day T, Tosey P. Beyond SMART? A new framework for goal setting. The Curriculum Journal. 2011 Dec;22(4):515-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.627213

32. Lee, KPW. Planning for success: Setting SMART goals for study. British Journal of Midwifery. 2010 Nov;18(11):744-6. doi: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2010.18.11.79568

33. Clarke SP, Crowe TP, Oades LG, Deane FP. Do goal-setting interventions improve the quality of goals in mental health services? Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32(4):292-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.2975/32.4.2009.292.299

34. Bovend'Eerdt TJ, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009 Apr;23(4):352-61. Erratum in: Clin Rehabil. 2010 Apr;24(4):382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101741

35. Jung LA. Writing SMART Objectives and Strategies That Fit the ROUTINE. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 2007;39(4):54-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990703900406

36. van Herten LM, Gunning-Schepers LJ. Targets as a tool in health policy. Part I: Lessons learned. Health Policy. 2000 Aug;53(1):1-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00081-6

37. Doran, GT. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review. 1981 Nov;70(11):35-6.

38. Baker A, Cornwell P, Gustafsson L, Lannin NA. An exploration of goal-setting practices in Queensland rehabilitation services. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Aug;44(16):4368-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1906957

39. Dejonckere PH, Bradley P, Clemente P, Cornut G, Crevier-Buchman L, Friedrich G, et al. A basic protocol for functional assessment of voice pathology, especially for investigating the efficacy of (phonosurgical) treatments and evaluating new assessment techniques. Guideline elaborated by the Committee on Phoniatrics of the European Laryngological Society (ELS). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Feb;258(2):77-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s004050000299

40. Hirano M. Objective evaluation of the human voice: clinical aspects. Folia Phoniatr (Basel). 1989;41(2-3):89-144. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000265950

41. Krasny-Pacini A, Hiebel J, Pauly F, Godon S, Chevignard M. Goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation: a literature-based update. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2013 Apr;56(3):212-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2013.02.002

42. Krasny-Pacini A, Evans J, Sohlberg MM, Chevignard M. Proposed Criteria for Appraising Goal Attainment Scales Used as Outcome Measures in Rehabilitation Research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016 Jan;97(1):157-70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.424

43. Ruble L, McGrew JH, Toland MD. Goal attainment scaling as an outcome measure in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 Sep;42(9):1974-83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1446-7

44. Hersh D, Sherratt S, Howe T, Worrall L, Davidson B, Ferguson A. An analysis of the “goal” in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology. 2012;26(8):971-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.684339

45. Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: A general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J. 1968 Dec;4(6):443-53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01530764

46. Hamilton J, Sohlberg MM, Turkstra L. Opening the black box of cognitive rehabilitation: Integrating the ICF, RTSS, and PIE. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2022 Sep 21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12774

47. Kucheria P, Moore Sohlberg M, Machalicek W, Seeley J, DeGarmo D. A single-case experimental design investigation of collaborative goal setting practices in hospital-based speech-language pathologists when provided supports to use motivational interviewing and goal attainment scaling. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2022 May;32(4):579-610. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1838301

48. Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009 Apr;23(4):362-70. Erratum in: Clin Rehabil. 2010 Feb;24(2):191. PMID: 19179355. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101742

49. Marsland E, Bowman J. An interactive education session and follow-up support as a strategy to improve clinicians' goal-writing skills: a randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010 Feb;16(1):3-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01104.x

50. Bowman J, Mogensen L, Marsland E, Lannin N. The development, content validity and inter-rater reliability of the SMART-Goal Evaluation Method: A standardised method for evaluating clinical goals. Aust Occup Ther J. 2015 Dec;62(6):420-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12218

51. Dagnino SJ. Tipos de datos y escalas de medida. Revista Chilena de Anestesia. 2014;43(2): doi: https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv43n02.06

52. Forrest M, Andersen B. Ordinal scale and statistics in medical research. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986 Feb 22;292(6519):537-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6519.537

53. Coronado, J. Escalas de medición. Paradigmas. 2007 Jul;2(2):104-25. Disponible en: https://publicaciones.unitec.edu.co/index.php/paradigmas/article/view/21

54. Law M. Measurement in Occupational Therapy: Scientific Criteria for Evaluation. Can J Occup Ther. 1987;54(3):133-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/000841748705400308

55. Besser MC, Moncada L. Proceso Psicoterapéutico Desde la Perspectiva de Terapeutas que Tratan Trastornos Alimentarios: Un Estudio Cualitativo. Psykhe. 2013;22(1):69-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.22.1.633

56. Caro-Gabalda I. El cambio terapeútico a través del modelo de asimilación : su aplicación en la terapia lingüística de evaluación. Rev de Psicopatol y Psicol Clin. 2011;16(3):169-88. doi: https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.16.num.3.2011.10360

57. Patel RR, Awan SN, Barkmeier-Kraemer J, Courey M, Deliyski D, Eadie T, et al. Recommended Protocols for Instrumental Assessment of Voice: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Expert Panel to Develop a Protocol for Instrumental Assessment of Vocal Function. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2018Aug 6;27(3):887-905. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0009

58. Kreiman J, Gerratt BR, Garellek M, Samlan R, Zhang Z. Toward a unified theory of voice production and perception. Loquens. 2014 Jan;1(1):e009. doi: https://doi.org/10.3989/loquens.2014.009

59. Azul D, Hancock AB, Nygren U. Forces Affecting Voice Function in Gender Diverse People Assigned Female at Birth. J Voice. 2021 Jul;35(4):662.e15-662.e34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.01.001

60. Azul D, Hancock AB. Who or what has the capacity to influence voice production? Development of a transdisciplinary theoretical approach to clinical practice addressing voice and the communication of speaker socio-cultural positioning. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020 Oct;22(5):559-70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2019.1709544

61. Colton RH, Casper JK, Leonard R. Understanding Voice Problems. LWW; 2011. 496 p.

62. Mathieson L. Greene and Mathieson’s the voice and its disorders. Londres: Whurr; 2001. 750 p.

63. Coupland N. Social Context, Style, and Identity in Sociolinguistics. In: Holmes J, Hazen K, editors. Research Methods in Sociolinguistics: a Practical Guide. Wiley Blackwell; 2014, p. 290-303.

64. Ahearn LM. Agency and language. In: Jaspers J, Östman J, Verschueren J, editors. Society and language use. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2010, p. 28-48.

65. Podesva RJ. Phonation type as a stylistic variable: The use of falsetto in constructing a persona. Journal of Sociolinguistics. 2007;11(4):478-504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00334.x

66. Bucholtz M, Hall K. Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies. 2005;7(4-5):585-614. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407

67. Agha A. The social life of cultural value. Language & Communication. 2003;23(3-4):231-73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0271-5309(03)00012-0

68. Rice DB, McIntyre A, Mirkowski M, Janzen S, Viana R, Britt E, et al. Patient-Centered Goal Setting in a Hospital-Based Outpatient Stroke Rehabilitation Center. PM R. 2017 Sep;9(9):856-65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.12.004

69. Azul D. Transmasculine people's vocal situations: a critical review of gender-related discourses and empirical data. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2015 Jan-Feb;50(1):31-47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12121

70. Azul D. Gender-related aspects of transmasculine people's vocal situations: insights from a qualitative content analysis of interview transcripts. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2016 Nov;51(6):672-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12239

71. Farías P. Ejercicios que restauran la función vocal (observaciones clínicas). 2nd ed. Akadia Editorial. 2020. 240 p.

72. Gillespie AI, Gartner-Schmidt J. Voice-Specialized Speech-Language Pathologist's Criteria for Discharge from Voice Therapy. J Voice. 2018 May;32(3):332-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.05.022

73. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

74. Windschitl M. Folk theories of "inquiry" How preservice teachers reproduce the discourse and practices of an atheoretical scientific method. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2004;41(5):481-512. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20010

75. Jaakkola E. Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Review. 2020;10:18-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

76. Benoot C, Hannes K, Bilsen J. The use of purposeful sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: A worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Feb 18;16:1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0114-6

77. Suri H. Purposeful Sampling in Qualitative Research Synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal. 2011;11(2):63-75. doi: https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ1102063

78. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. SAGE Publications; 2014. 832 p.

79. Martins RH, Tavares EL, Ranalli PF, Branco A, Pessin AB. Psychogenic dysphonia: diversity of clinical and vocal manifestations in a case series. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Nov-Dec;80(6):497-502. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.09.002

80. Willinger U, Aschauer HN. Personality, anxiety and functional dysphonia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(8):1441-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.011

81. MacCallum JK, Zhang Y, Jiang JJ. Vowel selection and its effects on perturbation and nonlinear dynamic measures. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2011;63(2):88-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000319786

82. Jiang JJ, Zhang Y, McGilligan C. Chaos in voice, from modeling to measurement. J Voice. 2006 Mar;20(1):2-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.01.001

83. Titze IR. Voice training and therapy with a semi-occluded vocal tract: rationale and scientific underpinnings. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006 Apr;49(2):448-59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2006/035)

84. Boone DR. Dismissal criteria in voice therapy. J Speech Hear Disord. 1974 May;39(2):133-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.3902.133

85. Scobbie L, McLean D, Dixon D, Duncan E, Wyke S. Implementing a framework for goal setting in community based stroke rehabilitation: a process evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 May 24;13:190. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-190

86. Rosewilliam S, Roskell CA, Pandyan AD. A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2011 Jun;25(6):501-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510394467

87. Desjardins M, Halstead L, Cooke M, Bonilha HS. A Systematic Review of Voice Therapy: What "Effectiveness" Really Implies. J Voice. 2017 May;31(3):392.e13-392.e32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.10.002

88. Schneider S, Frens R. Training four-syllable CV patterns in individuals with acquired apraxia of speech: Theoretical implications. Aphasiology. 2005;19(3-5):451-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030444000886

89. Maas E, Barlow J, Robin D, Shapiro L. Treatment of sound errors in aphasia and apraxia of speech: Effects of phonological complexity. Aphasiology. 2002;16(4-6):609-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000266

90. Schmidt RA, Lee TD. Motor Control and Learning. A Behavioral Emphasis. Human Kinetics Publishers; 2011. 592 p.

91. Maas E, Robin DA, Austermann Hula SN, Freedman SE, Wulf G, Ballard KJ, et al. Principles of motor learning in treatment of motor speech disorders. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2008 Aug;17(3):277-98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2008/025)

92. Grampurohit N, Mulcahey MJ. Outcome measures. In Abzug JM, Kozin S, Neiduski R, editors. Pediatric Hand Therapy. Elsevier, 2019. p. 31-56.

93. Diehm E. Writing Measurable and Academically Relevant IEP Goals With 80% Accuracy Over Three Consecutive Trials. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 2017;2(16):34-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/persp2.SIG16.34

94. Moore R. Beyond 80-Percent Accuracy. The ASHA Leader. 2018;23(5):6-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FMP.23052018.6

95. Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied Behavior Analysis. Pearson UK; 2020. 952 p.

96. Richling SM, Williams WL, Carr JE. The effects of different mastery criteria on the skill maintenance of children with developmental disabilities. J Appl Behav Anal. 2019 Jul;52(3):701-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.580

97. Love JR, Carr JE, Almason SM, Petursdottir AI. Early and intensive behavioral intervention for autism: A survey of clinical practices. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(2):421-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2008.08.008

98. Longino E, Richling SM, McDougale CB, Palmier JM. The Effects of Mastery Criteria on Maintenance: A Replication With Most-to-Least Prompting. Behav Anal Pract. 2021 Mar 15;15(2):397-405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00562-y

99. Fuller JL, Fienup DM. A Preliminary Analysis of Mastery Criterion Level: Effects on Response Maintenance. Behav Anal Pract. 2018;11(1):1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-017-0201-0

100 Haq SS, Kodak T. Evaluating the effects of massed and distributed practice on acquisition and maintenance of tacts and textual behavior with typically developing children. J Appl Behav Anal. 2015;48(1):85-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.178

101 Kocher CP, Howard MR, Fienup DM. The effects of work-reinforcer schedules on skill acquisition for children with autism. Behav Modif. 2015 Jul;39(4):600-21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445515583246

102 McDougale CB, Richling SM, Longino EB, O'Rourke SA. Mastery Criteria and Maintenance: a Descriptive Analysis of Applied Research Procedures. Behav Anal Pract. 2019 May 29;13(2):402-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00365-2

103 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Assessment of Voice Disorders . The Association; . Available from: https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/voice-disorders/#collapse_5

104 McAlister S, Yanushevskaya I. Voice assessment practices of speech and language therapists in Ireland. Clin Linguist Phon. 2020;34(1-2):29-53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2019.1610798

105 Joshi A. A Comparison of the s/z Ratio to Instrumental Aerodynamic Measures of Phonation. J Voice. 2020 Jul;34(4):533-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.02.014

106 Poburka BJ, Patel RR, Bless DM. Voice-Vibratory Assessment With Laryngeal Imaging (VALI) Form: Reliability of Rating Stroboscopy and High-speed Videoendoscopy. J Voice. 2017 Jul;31(4):513.e1-513.e14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.12.003

107 Hillman RE, Stepp CE, Van Stan JH, Zañartu M, Mehta DD. An Updated Theoretical Framework for Vocal Hyperfunction. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020 Nov 12;29(4):2254-60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00104

108 Husson R. Le chant. París: Presses Universitaires de France; 1962. 126 p.

109 Zaman J, Chalkia A, Zenses AK, Bilgin AS, Beckers T, Vervliet B, et al. Perceptual variability: Implications for learning and generalization. Psychon Bull Rev. 2021 Feb;28(1):1-19. doi: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01780-1

110 Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012 Oct;92(4):1651-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00048.2011

111 Héroux ME, Butler AA, Robertson LS, Fisher G, Gandevia SC. Proprioception: a new look at an old concept. J Appl Physiol. 2022 Mar 1;132(3):811-4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00809.2021

112 Roa-Ordóñez HG, Quintana UB, Aponte-Ovalle JJ. Pedagogía de la propiocepción corporal en el cantante. Civilizar. 2020;20(38):11-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.22518/jour.ccsh/2020.1a05

113 López J. Protocolo de entrenamiento vocal fonoaudiológico para cantantes: Vocalical. Areté. 2019 Dec;19(2):61-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.33881/1657-2513.art.19207

114 Le Huche F, Allali A. La Voz: Terapéutica de los Trastornos Vocales. Volumen 4. Elsevier España; 2004. 195 p.

115 Ramos JS, Feniman MR, Gielow I, Silverio KCA. Correlation between Voice and Auditory Processing. J Voice. 2018 Nov;32(6):771.e25-771.e36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.08.011

116 Rodríguez-Parra MJ, Adrián JA, Casado JC. Voice therapy used to test a basic protocol for multidimensional assessment of dysphonia. J Voice. 2009 May;23(3):304-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.05.001

117 Behlau M, Madazio G, Feijó D, Azevedo R, Gielow I, Rehder M. Aperfeiçoamiento Vocal e Tratamento Fonoaudiológico das Disfonias. In Behlau M, editor. Voz O Livro do Especialista, Volume II. Revinter; 2010. p. 432-437.

118 Marks KL, Verdi A, Toles LE, Stipancic KL, Ortiz AJ, Hillman RE, et al. Psychometric Analysis of an Ecological Vocal Effort Scale in Individuals With and Without Vocal Hyperfunction During Activities of Daily Living. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2021 Nov 4;30(6):2589-604. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00111

119 Helou LB, Jennings JR, Rosen CA, Wang W, Verdolini Abbott K. Intrinsic Laryngeal Muscle Response to a Public Speech Preparation Stressor: Personality and Autonomic Predictors. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2020 Sep 15;63(9):2940-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-19-00402

120 Helou LB, Wang W, Ashmore RC, Rosen CA, Verdolini Abbot K. Intrinsic laryngeal muscle activity in response to autonomic nervous system activation. Laryngoscope. 2013 Nov;123(11):2756-65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24109

121 Dietrich M, Andreatta RD, Jiang Y, Joshi A, Stemple JC. Preliminary findings on the relation between the personality trait of stress reaction and the central neural control of human vocalization. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012 Aug;14(4):377-89. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.688865

122 Dietrich M, Verdolini Abbott K. Vocal function in introverts and extraverts during a psychological stress reactivity protocol. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012 Jun;55(3):973-87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0344)

123 Mathieson L, Hirani SP, Epstein R, Baken RJ, Wood G, Rubin JS. Laryngeal manual therapy: a preliminary study to examine its treatment effects in the management of muscle tension dysphonia. J Voice. 2009 May;23(3):353-66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.10.002

124 Martinez CC, Lemos IO, Madazio G, Behlau M, Cassol M. Vocal parameters, muscle palpation, self-perception of voice symptoms, pain, and vocal fatigue in women with muscle tension dysphonia. Codas. 2021 Aug 2;33(4):e20200035. Portuguese, English. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20202020035

125 Calais-Germain B. La respiración: anatomía para el movimiento. Tomo IV. El gesto respiratorio. La liebre de marzo; 2007. 215 p.

126 Chaitow L, Walker DeLany J. Aplicación clínica de las técnicas neuromusculares. Tomo I. Badalona: Paidotribo; 2006. 274 p.

127 Angsuwarangsee T, Morrison M. Extrinsic laryngeal muscular tension in patients with voice disorders. J Voice. 2002 Sep;16(3):333-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00105-4

128 Lucchini E, Ricci Maccarini A, Bissoni E, Borragan M, Agudo M, González MJ, et al. Voice Improvement in Patients with Functional Dysphonia Treated with the Proprioceptive-Elastic (PROEL) Method. J Voice. 2018 Mar;32(2):209-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.05.018

129 Borragán A, Lucchini E, Agudo M, González M, Ricci A. Il Metodo Propriocettivo Elastico (PROEL) nella terapia vocale. Acta Phoniatrica Latina. 2008;30(1):18-50. Disponible en: https://www.voicecentercesena.it/assets/file/6364d3f0f495b6ab9dcf8d3b5c6e0b01.pdf

130 Lowell SY, Colton RH, Kelley RT, Auld M, Schmitz H. Isolated and Combined Respiratory Training for Muscle Tension Dysphonia: Preliminary Findings. J Voice. 2022 May;36(3):361-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.06.013

131 Van Lierde KM, Claeys S, De Bodt M, Van Cauwenberge P. Outcome of laryngeal and velopharyngeal biofeedback treatment in children and young adults: a pilot study. J Voice. 2004 Mar;18(1):97-106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2002.09.001

132 González R, Donoso A. Programa de rehabilitación fonoaudiológica para pacientes afásicos. Revista Chilena de Fonoaudiología. 2000;2(3):35-48.

Appendix 1

Extended version of the taxonomy of outcome criteria.